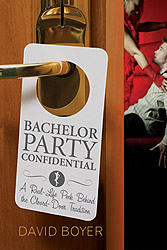

Bachelor Party Confidential

Sunday, April 29th, 2007Two strippers, a dwarf, an S&M clown, a Vegas bouncer and a pair of wedding planners. Not the start of a dirty joke, but in fact just a handful of the more than 100 people from all over the globe I talked to for my book, Bachelor Party Confidential: A Real Life-Peek Behind the Closed-Door Tradition.  In my journey to dig into this incredible, timeless, messy tradition, I met men from different generations, classes and backgrounds. I spoke with religious grooms, wary brides and the fathers who love them. Each offered a unique point of view and, together, their stories revealed the first full portrait of this secret ritual.

In my journey to dig into this incredible, timeless, messy tradition, I met men from different generations, classes and backgrounds. I spoke with religious grooms, wary brides and the fathers who love them. Each offered a unique point of view and, together, their stories revealed the first full portrait of this secret ritual.

I was never looking to blow the whistle on this rare chance for male-bonding, nor was I planning to defend it: I just wanted to know what the bachelor party tradition meant to each of them, how it’s affected their relationships and how it’s changed over the years.

I offered total anonymity to everyone. In return, they served up painful, poignant, secret, and salacious stories—stories I sensed that many had been dying to tell for years. Here are five excerpts to whet your appetite. Pour yourself a drink and prepare, as they say in the wedding biz, for better or for worse.

Check out this Flickr stream of bachelor party photos.

Have a bachelor party story? Tell SMITH

The Stories:

The Original Bachelor

The Vegas Strip Club Manager

The Born-Again Best Man

The Remorseful Best Man

The Buck’s Prank

THE ORIGINAL BACHELOR

Henry B. partied in 1922

While every other story in the book is from firsthand interviews, this piece of history comes from the archive of the Federal Writers’ Project of the Work Progress Administration (WPA). This WPA interview with HENRY B., who was born in Woonsocket, Rhode Island, “in a basement” in 1898, suggests that guys have been having a sex-tinged last hurrah for some time. And that your great-granddad may have partied more than you suspected.

I came through [World War I] without a scratch. When I was demobilized, I returned to Woonsocket. I went to work in the Woonsocket Rubber Co. as a trucker. This job only paid twenty-two dollars [a week], but I was compensated in another way, for while working there I met the girl that later became my wife.

In 1922 the mills started running full time and I was able to obtain employment as a weaver in the Montrose Mill. Shortly after I started working there, I married Alice. I was twenty-four years old and [she] was twenty.

In 1922 the mills started running full time and I was able to obtain employment as a weaver in the Montrose Mill. Shortly after I started working there, I married Alice. I was twenty-four years old and [she] was twenty.

Two nights before the wedding, my friends held a stag party for me. They hired a hall, and about one hundred men gathered there to celebrate my marriage. Father Didion, my pastor, who knew everything that happened in the parish, arrived at the hall early and, to the consideration of the other guests, he sat down and started eating. After the meal, he made a short speech as to the duties of a married man. He then proposed a toast to the young couple and showed that he was the soul of discretion by announcing that it was getting late and he had some duties to attend to at the parish house. Then he left. Everyone in the hall felt relieved, as most of the acts that they had hired in Boston were of the ’strip-tease’ type and it was not possible to have them performed while good Father was in the hall.

THE VEGAS STRIP CLUB MANAGER

Lola R. has witnessed hundreds of bachelor parties

Of course, some bachelor parties are exactly as you imagine: Vegas, strippers, drugs and alcohol. LOLA R. is a cocktail manager at one of the most popular gentlemen’s clubs in the city and she talked to me about what she’s seen behind the curtains of her club’s legendary VIP rooms.

Of course, some bachelor parties are exactly as you imagine: Vegas, strippers, drugs and alcohol. LOLA R. is a cocktail manager at one of the most popular gentlemen’s clubs in the city and she talked to me about what she’s seen behind the curtains of her club’s legendary VIP rooms.

I work in a VIP area. They’re private booths that have curtains completely around them. I’ve walked in on all different levels of undress. And when people say there’s no sex in these rooms, well, they either haven’t spent enough money or they haven’t met a stripper that’s good enough at hiding it.

I’ve probably seen more than 500 bachelor parties. I don’t really like them. Not to sound shallow, but at this point, being in Vegas for the past three years, I’ve seen the amount of money that goes through this town—and bachelor parties just don’t spend the kind of money that other people do! They’re on a budget in a big way, but they want the VIP treatment.

When bachelors first get here, they all say, “I don’t really go to strip clubs” and “I’m only here because my friends made me come.” I can’t tell you how many times a night I hear that. A few shots down the road and all of a sudden they’re professionals: they’re getting dances, they’re going into private areas, and it’s a whole different story.

We had this one bachelor party—it wasn’t very big, only about eight guys—but it was the guy getting married, his dad and grandfather, and his father-in-law-to-be and his grandfather-in-law-to-be. They all ended up in a VIP booth. And I walked back there and I’m watching grandpa feel up a stripper. I was like, “Are you kidding? Isn’t this just a little weird? Does anybody else have a problem with it?” I really think it’s that whole male-bonding, loyalty thing. And it’s like your acceptance into the family. But I wouldn’t be able to sit next to my mother-in-law and be able to get a lap dance.

I am actually divorced. I was pretty young when I got married. My whole thing was, “You’re going to have strippers, that’s cool. But if I find out you slept with them, the wedding’s off.” I don’t think I would react that way now… I tried to do the whole controlling no-strippers-and-you-can’t-do-this-and-you-can’t-do-that routine.

But it all went on: They ended up having four strippers, got a hotel room, games were played. And everything else that I said I didn’t want to happen, happened. I think there’s nothing that you can do to prevent it. No matter what the groom says, his friends are still gonna do it; there isn’t a friend in the world that loves him enough to forego a bachelor party.

Ultimately, I do think bachelor parties are worse in Vegas because you have that ad campaign: “What happens in Vegas, stays in Vegas.” People forget that some of us actually live here, and have lives and kids and families. And being a woman in Vegas, people automatically think you are a prostitute; I’m propositioned constantly.

THE BORN-AGAIN BEST MAN

Peter M. planned a Christian Bachelor Party

PETER M., a preacher’s son, grew up in the church. As the pastor that runs the Men’s Ministry at the Midwestern megachurch helmed by this father, Peter is sometimes asked for advice about bachelor parties. He tends to quote two pieces of scripture: “Bad company corrupts good morals.” (Corinthians 15:33) and “The spirit is indeed willing, but the flesh is weak.” (Matthew 26:41) Explains the pastor, “If it compromises your morals, you need to get out of there.” He didn’t have a bachelor party when he got married nine years ago. “I was twenty-one and I was a virgin,” he says. “I didn’t need a bachelor party to remind me what I was leaving—I couldn’t wait to leave it, man.” A few years ago, the bachelor party novice had to plan one for his cousin.

PETER M., a preacher’s son, grew up in the church. As the pastor that runs the Men’s Ministry at the Midwestern megachurch helmed by this father, Peter is sometimes asked for advice about bachelor parties. He tends to quote two pieces of scripture: “Bad company corrupts good morals.” (Corinthians 15:33) and “The spirit is indeed willing, but the flesh is weak.” (Matthew 26:41) Explains the pastor, “If it compromises your morals, you need to get out of there.” He didn’t have a bachelor party when he got married nine years ago. “I was twenty-one and I was a virgin,” he says. “I didn’t need a bachelor party to remind me what I was leaving—I couldn’t wait to leave it, man.” A few years ago, the bachelor party novice had to plan one for his cousin.

My cousin was a little bit of a late bloomer: he didn’t get married until he was twenty-eight. And I planned his bachelor party; I wanted to do something that was special for him. I didn’t study the whole bachelor party thing; I just began to think, “How do you throw a bachelor party for a guy that believes in God?”

I decided to center the entire party around what he likes—obviously not from a carnal standpoint. My cousin likes to eat, so we took him to a Japanese steakhouse; he loves to golf, we took him golfing; he loves movies, so we rented his three favorites; he likes to play cards—this is maybe where you get into a grey area—so we took him to a casino for an hour and a half.

The fact that I took him to a casino was a big deal. For text-studied Christians, obviously there’s no gambling. But I wasn’t trying to be religious and I wasn’t trying to be legalistic and predictable. That’s one thing that always drives me nuts: when you have Christians that get together and everything’s got to be a scripture, three points and a poem. Just have fun for a change! And that’s why I did it for him… It was just a fun day with his most favorite people, and he’ll never forget it.

That’s the thing about the Christian bachelor party: you remember what you’ve done and you don’t have to worry about telling people what you did. There was no drinking or carnal or questionable activity involved.

I think the cliche bachelor party is very disappointing; I don’t see what’s enjoyable about getting a person you call a friend all liquored up, wasting your money and watching him consume something—that being alcohol, that being a lady, that being a lap dance—the night or the weekend before he’s getting married.

You can say the same thing about us going to the casino—maybe mediocrity ruled. But I put together the party so quick that I didn’t have time to bring in a dealer and say, “Let’s play with Oreos” or something goofy or cheesy. So, I thought, “Maybe going this one time won’t hurt us.”

THE REMORSEFUL BEST MAN

Brent P. planned a stag that ended badly

Maybe it shouldn’t be shocking that injuries and deaths occur at bachelor parties. In the last year alone, I have read stories about fatal car crashes, savage beatings and a deadly stabbing. And Sean Bell was killed after police shot him 55 times when he and his friends were leaving a strip club the night before he was supposed to get married. BRENT P. tries not to dwell on what happened at his buddy’s bachelor party more than two decades ago. But he decided to talk with me, in part, because he hopes his story will serve as a warning to others.

Maybe it shouldn’t be shocking that injuries and deaths occur at bachelor parties. In the last year alone, I have read stories about fatal car crashes, savage beatings and a deadly stabbing. And Sean Bell was killed after police shot him 55 times when he and his friends were leaving a strip club the night before he was supposed to get married. BRENT P. tries not to dwell on what happened at his buddy’s bachelor party more than two decades ago. But he decided to talk with me, in part, because he hopes his story will serve as a warning to others.

One of my best friends from high school was getting married to a girl he had met at the seafood restaurant that we all worked at in Phoenix.

I decided to throw his bachelor party and we were going to go to Las Vegas. So I got a bus… and we were gonna leave in the morning, to have a night in Vegas to party and come back the next day. On the way, we planned to stop at a lake.

So we were on the bus, and you know, we had beers in coolers. One of the employees who worked with us was a younger busboy named Tommy. I was unaware that he’d gotten into the coolers and started drinking.

We get to this lake and they have a water park with slides and ropes and things you can jump off of. It’s a hot day and the cicadas are going. We start swimming around and Tommy jumps in headfirst. Somebody had seen him jump in, but it didn’t occur to anybody that he didn’t come up. A few minutes go by and the groom’s brother says, “Where’s Tommy?”

We can’t find him and we start thinking maybe he’s underwater. So people started diving down, feeling the murky bottom. And it took a few minutes and finally someone who wasn’t with our group pulled him up by the wrist and said, “I got him.” They called the paramedics, who took maybe twenty minutes to get there, because we’re in the middle of the desert. The paramedics came and somebody said they got a heartbeat, and everybody cheered. They took Tommy to the nearest hospital… and we followed in the bus. We waited around the hospital for a couple of hours, and they finally came out and told us that he was dead.

Two of the schmucks that were on the bus said, “What do we do? Keep going to Vegas? Tommy would have wanted us to.” And I looked at these guys and I said, “You’re out of your minds. We’re not going to Vegas, somebody just died. We’ve got to go home and somebody’s got to tell his parents.”

So we got on the bus and we went back to Phoenix. Eventually Tommy’s parents were told and he was buried. But nothing ever happened: they didn’t sue the lake or anything like that… It crosses my mind every once in a while, but it didn’t get to me, or haunt me, or anything like that; it’s just a sad episode. It shouldn’t have happened.

THE BUCK’S PRANK

Liam K. does it Aussie style

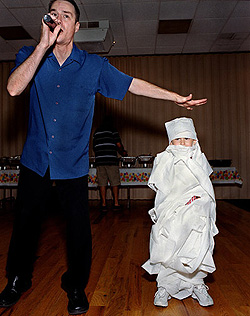

Each country and community puts its own twist on the bachelor party ritual. The centerpiece of the Australian bucks party, for instance, is a sometimes elaborate, somewhat sadistic prank. Thirty-one-year-old LIAM K., who admits, “I look forward to the bucks more than the wedding,” told recounts one such prank that quickly became a staple of my cocktail-party repertoire.

The most memorable one was for a guy I play rugby with. We all met at 10 AM and started by smoking dope. We had already decided to play “pub golf” around Sydney; (I suspect you don’t know what that is, mate). There’s eighteen pubs, and each pub has a different par to it, like a par three or a par four. You go into each pub for twenty minutes or so. And if it’s a par three, you have to drink three beers while you’re there. But if you get four beers in you, then you go one-under par. And it’s a competition to see who can have the lowest score.

The most memorable one was for a guy I play rugby with. We all met at 10 AM and started by smoking dope. We had already decided to play “pub golf” around Sydney; (I suspect you don’t know what that is, mate). There’s eighteen pubs, and each pub has a different par to it, like a par three or a par four. You go into each pub for twenty minutes or so. And if it’s a par three, you have to drink three beers while you’re there. But if you get four beers in you, then you go one-under par. And it’s a competition to see who can have the lowest score.

By the end of the eighteen holes—I mean pubs—it’s pretty severe. For this bucks, we had a bus taking us from one to the other. By about 7 PM the groom was unconscious. The normal thing would have been to strip him and leave him somewhere. But the best man said, “Why don’t we take him to the hospital and put a cast on his arm and pretend he’s broken it and we’ll tell him the next day that it’s a joke.” By the time we got to the hospital, it turned into, “Fuck it, we’re gonna put a cast on his whole leg.” From his ankle to the top of his hip. And because one of the guys we play rugby with is a doctor at the hospital, they let us do it.

The groom woke up the next day, and we told him he fell down the stairs at a pub and broke his leg. He didn’t know it wasn’t broken, because his leg was in the cast and he couldn’t move it.

The wedding was two or three days later, so he went through the wedding on crutches with a cast. For his honeymoon, he went to Fiji. He was there for ten days and didn’t swim because he figured he couldn’t get his cast wet.

We told him when he got back. He didn’t talk to us for a long time. We’re still on bad terms with his missus—and that was five fuckin’ years ago. He laughs about it now, but he can still get pissed if we all laugh about it too much.

Text copyright © 2007 by David Boyer. Published by Simon Spotlight Entertainment, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Printed with permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Want your very own copy of BACHELOR PARTY CONFIDENTIAL? Buy it now Have a bachelor party story? Tell SMITH

A decade ago, when Princess Diana was still alive and in the midst of her ignoble divorce proceedings, I happened to find myself in the lobby of the Victoria Albert Museum, London, nursing a crushing hangover. My goal was to find the museum’s Frank Lloyd Wright Rooms improbably disassembled and transported there, pine panel and all, from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

A decade ago, when Princess Diana was still alive and in the midst of her ignoble divorce proceedings, I happened to find myself in the lobby of the Victoria Albert Museum, London, nursing a crushing hangover. My goal was to find the museum’s Frank Lloyd Wright Rooms improbably disassembled and transported there, pine panel and all, from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

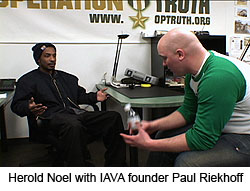

Unemployment wasn’t the only problem dogging Noel, who also returned with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). “I was always jumping out of my sleep, scaring the kids, walking around the house in the middle of the night like I’m looking for something—so I had to move out,” says Noel, who would later become the subject of the award-winning documentary

Unemployment wasn’t the only problem dogging Noel, who also returned with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). “I was always jumping out of my sleep, scaring the kids, walking around the house in the middle of the night like I’m looking for something—so I had to move out,” says Noel, who would later become the subject of the award-winning documentary  When I came back, it was unreal to me because I was supposed to be dead. That story I just told you—that was one event, just one of many. And that’s just the beginning, just a light coat. I didn’t even tell you the horror. When I first got back, I couldn’t believe I was alive. I couldn’t believe I was looking at people. I couldn’t believe I was hugging my kids. I couldn’t even touch my kids at a point, because I had seen kids die over there. I was looking at a little girl in Iraq who got her head blown off, and I’m looking at my daughter. The girl was the same age as my daughter.

When I came back, it was unreal to me because I was supposed to be dead. That story I just told you—that was one event, just one of many. And that’s just the beginning, just a light coat. I didn’t even tell you the horror. When I first got back, I couldn’t believe I was alive. I couldn’t believe I was looking at people. I couldn’t believe I was hugging my kids. I couldn’t even touch my kids at a point, because I had seen kids die over there. I was looking at a little girl in Iraq who got her head blown off, and I’m looking at my daughter. The girl was the same age as my daughter.