Katherine Sharpe is a SMITH contributing editor, editor of a literary magazine 400 Words, as well as an editor at Seed Media Group.

During my childhood, my father was reluctant to buy himself new things. It’s not that he couldn’t afford them. We had plenty of money–not tons, but enough to pay for our own house, a bungalow with two-and-a-half bedrooms and dark bull’s-eye moldings around the windows and doors. Both of my parents had jobs: my mother as an English professor at the community college, my father as a lobbyist for an environmental group. Still, my father went around with holes in his undershirts and socks, and cardboard buffering the holes in his wingtip shoes.

I remember my father dressing for work. He wore white 50-50 undershirts with short sleeves, several of them with so many holes that they looked like cobwebs slung across his back. My father’s large and pinkie toes peeped out of his dark nylon socks. The jersey fabric hung away in baggy arcs from the band of his tighty whities. I remember these things because my mother complained about them from time to time. “Your father won’t buy himself new shirts,” she said. “And he’s starting to look like a bum.”

Nightly, at the dinner table, my father would spill something on his shirt or tie. A blot of tomato sauce or a fleck of butter would leap from plate to fabric, and then my father himself would leap up from his chair, bellow with rage, and dash to the sink to flush water over the offending morsel. Sometimes he would come back to the table with a water-darkened spot on his front. Other times he would retire to the bedroom, making loud, angry sounds as he rubbed detergent into the stain and changed his shirt. This performance seemed to repeat itself night after night, with uncanny persistence. Maybe my child-brain has distorted the memory, making something that only happened a few times seem to have been a regular occurrence, but this for me is the archetypal family dinner of the time.

Mostly what I remember from these spilling episodes is my father’s anger. It was never “Oops.” It was “God damn it. God damn it!” My father’s shouting voice is powerful and rich in bass. For a kid it can be frightening. But he always returned to the dinner table, and we always finished our meals more or less amicably. He was not angry at us. It’s not us he was angry at.

From that era I also remember my father coming home from work. It seems to me, looking back, that it was always dark outside when he came home, and always raining. It’s like this: My father wears his black wingtips and a tan trench coat. The trench coat is dappled with rainwater. I hear him come through the door, the weight of his footsteps on the pine floor. I drop the blocks and toys I am playing with in the back room, and run to throw my arms around his legs. My father is a tall man. I feel the bones in his legs and the raindrops cold on his coat, as I press my cheek into his knees.

Then my father comes into the kitchen. My mother stands near pots that bubble on the stove. The kitchen glows with the yellow-orange tones of lamplight reflecting off the dark wood floor, the brown melamine counters. The windows seem to have steamed up on the inside with condensation. We are having chuck steak with Worcestershire sauce, baked potatoes, green peas. We are having broccoli. Or chicken baked with canned tomatoes and slices from a roll of sausage. Or slender pork chops fried up with condensed cream of mushroom soup, and carrots cut into fat pennies.

In the kitchen, in the incandescent light, my mother and father embrace. He throws his arms around her. She squeezes back. They kiss on the mouth, but it is only a peck. My father’s tall frame bends down to my mother’s short one; she lifts her face up to meet his. Mostly, though, they just hold each other. My father’s height seems to take up all the vertical space in the room. “Oh Suzy,” he says. His day was hard. He’ll open a can of Black Label and, half an hour from now, he’ll spill condensed cream of mushroom down his blue oxford shirt and yell, God damn it!

In the mornings my father would sit and roll his coffee cup across his forehead, to ease his sinuses with the warmth. Simple enough: he had clogged sinuses; the heat helped. Still, there seemed to be something more to this gesture, too. As he rolled the mug across his forehead, my father gave off an aura of suffering. It wasn’t just his sinuses; he seemed to feel sluggish and blocked in a more global way, too. I see this looking back. It was inchoate then, but something I noticed, without the words to think it through.

My father was also a bather. He showered in the mornings, but sometimes he took a bath after work or on the weekends, for relaxation. He ran his baths very hot, and let the water run to the brim of the tub. He’d work the water taps with his toes, letting a trickle of straight-hot water flow constantly, to keep the temperature up as he marinated. He had cut a board to the exact width of the tub, so he’d have a surface to read in the bath or scribble on papers. Sometimes, for work, my father was called upon to go to conferences and give speeches. Even as a small child I understood that speechwriting was an ordeal for him. He fretted over it. My mother fretted over his fretting. He would retire to the bath for hours with stacks of paper, flipping them, marking lines out with a pen and adding notes in the margins. Steam on the walls and mirror again. Great gusts of humid air blowing down the hallway when he finally emerged. Post-Its with crabbed handwriting everywhere.

I didn’t realize what my father was like until he changed. Only after the change was I able to look back and identify the feeling that he gave off as anything other than an inevitability concerning either my father or fathers in general. There was a heaviness to his movements then, the way he came in the door after work, removed his cold, rain-flecked trench coat and hung it on top of the lumpy, over-full coat rack in the corner. A heaviness to the way he sat in his morning chair, rolling coffee across his forehead, or in his bath, shifting humid papers with worried concentration into piles.

+++

PERHAPS I AM BEING UNFAIR TO MY FATHER. He was like this. But people are complicated, of course, and he was like many other ways too. There is a picture in the family album. It’s a black and white eight-by-ten, which my mother snapped on her old Minolta. In the picture, I am three. My sister has just been born, and on this night, as the four of us are relaxing together in the living room, I am enjoying a respite from my new, big-sisterly jealousy. Someone has given us a package of novelty sponges shaped like the letters of the alphabet. My mother sits on the salt-and-pepper tweed sofa, my father and I on the hideous piebald shag rug on the floor. Everyone feels fine, even silly. Dad and I begin to play with the sponges. The letter ‘C’ fits on my nose, like a soft clamp. ‘G’ fits, with a little more stretching, on Dad’s. I laugh, and he laughs, crinkling his nose, the pores stretching and changing shape with his smile. We add letters to our fingers, toes, and ears, collapsing in the photo in laughter and delight.

I can’t remember when my dad changed, how old I was at the time. He changed because he went to a doctor and the doctor prescribed a pill for him to take. This wasn’t therapy, just a pharmaceutical affair. After go-rounds with several medications, my father and his doctor settled on an old-fashioned antidepressant that worked well for him, and my father changed, and that was that.

I don’t know how much of all this I understood at the time. But I do remember the change, how it was at once vivid and gentle. I remember the sense of the end of one era and the beginning of another: I turned into a sullen twelve-year-old and then a teenager. My father wasn’t cool anymore. We didn’t play blocks. I became too large and too old to ride on his shoulders and sit on his knees. He got a better job and, instead of returning home rumpled and splashed with rain, he began to stride confidently down the brick walk of our new house, past the rhododendrons, in to dinner. One day a sensory memory hit me, of the way that my father used to come home, moving as though someone had sewn gravel into his coat, and I remembered that those days had once existed and that they now were gone, the gleam on the dark wood floor, the steam on the windows, the games, my childhood, that era in my father’s life and the life of our family.

People who take antidepressants are fond of saying that their medication makes them feel “more like myself.” I suspect that this is, in part, a way of lessening the fear that taking a drug might make one less authentic. But I also think that it is an attempt to state a true feeling that people who take antidepressants have.

We said it. I remember my mother saying it at the time: he seems more like himself, somehow, now. And I understood instantly and intuitively what she meant. He seemed more like the man captured on film horsing around with his wife and daughters, clamping foam letters to his nose.

I don’t know if it’s really that simple to “feel more like oneself.” The statement that antidepressants make one more like oneself is a partial but not a whole truth. Both men were my father, himself: the warm, happy young dad with the alphabet sponges, and the sad man with the constellation of holes riddling the back of his thoroughly expired undershirt. Medicine allowed us to experience more of one version and less of another. It didn’t make my father a different person; it made him spend more time in a particular register of his personality.

Three weeks ago, I visited my parents at home. I spent a couple of hours in the car with my Dad, and our conversation ranged over many things: my attempts to become an adult without qualifiers, his new-retiree’s reflections on working and family life. He’s radiant these days, enjoying freedom, teaching himself how to make fine wood furniture. He says that he feels good about the work he did, his marriage, his children. He has not been making himself feel bad, as he has done in the past, by telling himself about the things he ought to have done or the contributions he ought to have made. Anything he would have changed? I asked, tensing for the answer. “I do regret having spent so many years being depressed,” he said, in his distinctive slow, deliberate way. We looked at each other, with love and a sudden bit of sheepishness, and then we both returned our eyes to the road.

Go to the Photos

Go to the Photos

When I graduated from UVA with a BA in History, I’d completed a degree in what I loved doing—writing and learning. But as I learned shortly thereafter, no one will pay you to write about the economic development of the post-Lenin Soviet Union unless you have a PhD. So, I went back to school and got a degree in computer science so that I could program, which, as it turns out, people will pay you for.

When I graduated from UVA with a BA in History, I’d completed a degree in what I loved doing—writing and learning. But as I learned shortly thereafter, no one will pay you to write about the economic development of the post-Lenin Soviet Union unless you have a PhD. So, I went back to school and got a degree in computer science so that I could program, which, as it turns out, people will pay you for.

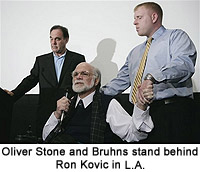

I personally disagree with the mentality of soldiers who return home from Iraq and wear half of their uniform with a pair of jeans or Hawaiian shorts. And they put black magic marker on their desert camouflage top and try to revive that type of 60s anti-war movement. I think it’s more effective if you conduct yourself in a professional manner and speak rationally and coherently and share your experiences in a professional way. I think that will get you further than if you go to Capitol Hill and disrupt a hearing and get arrested.

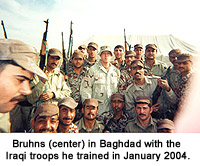

I personally disagree with the mentality of soldiers who return home from Iraq and wear half of their uniform with a pair of jeans or Hawaiian shorts. And they put black magic marker on their desert camouflage top and try to revive that type of 60s anti-war movement. I think it’s more effective if you conduct yourself in a professional manner and speak rationally and coherently and share your experiences in a professional way. I think that will get you further than if you go to Capitol Hill and disrupt a hearing and get arrested. In a way it is. A lot of veterans feel strongly about the policy, how the administration is conducting the war. It’s not a good policy. In a sense politics somehow gets into the discussion. But I think the real power from veterans comes from their experiences. When just regular vets have their voices heard. When the administration says one thing and they say, “Wait a minute, we’ve experienced something totally different.” I think that appeals more to the American public, because we’re not foreign policy experts. I don’t have a master’s degree in political science. We’re not all Capitol Hill staffers or elected officials. But what we do have is our experience, and no one can take that away from us.

In a way it is. A lot of veterans feel strongly about the policy, how the administration is conducting the war. It’s not a good policy. In a sense politics somehow gets into the discussion. But I think the real power from veterans comes from their experiences. When just regular vets have their voices heard. When the administration says one thing and they say, “Wait a minute, we’ve experienced something totally different.” I think that appeals more to the American public, because we’re not foreign policy experts. I don’t have a master’s degree in political science. We’re not all Capitol Hill staffers or elected officials. But what we do have is our experience, and no one can take that away from us. There was a night in Iraq where a roadside bomb had gone off and it disabled one the Humvees our scout platoon was driving around. Luckily nobody was injured. Part of my job was to respond to any disturbance in the area, so they called my squad out there, and some of the local Iraqis said that the people who planted the bomb were in the house next door to them. So we went in the house fast and furious, gathered all the people in the house and put them in the living room. There was a diverse crowd—some old men, some women, some children, there were some men in their 30s, and some teenage boys. Everybody was scared. I wasn’t scared. I could tell we definitely had the upper hand. We had 10 troops in there, locked and loaded, fingers on the trigger, and we had this machine that could detect bomb-making residue on the hands of insurgents.

There was a night in Iraq where a roadside bomb had gone off and it disabled one the Humvees our scout platoon was driving around. Luckily nobody was injured. Part of my job was to respond to any disturbance in the area, so they called my squad out there, and some of the local Iraqis said that the people who planted the bomb were in the house next door to them. So we went in the house fast and furious, gathered all the people in the house and put them in the living room. There was a diverse crowd—some old men, some women, some children, there were some men in their 30s, and some teenage boys. Everybody was scared. I wasn’t scared. I could tell we definitely had the upper hand. We had 10 troops in there, locked and loaded, fingers on the trigger, and we had this machine that could detect bomb-making residue on the hands of insurgents.