Back Home with Jacob Schick from HBO’s Alive Day Memories: Home From Iraq

By Michael Slenske

Michael Slenske’s last Back Home From Iraq piece was an interview with Marine reservist Todd Bowers.

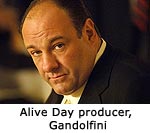

The numbers are dizzying—nearly 4,000 U.S. troops have died in Iraq and Afghanistan, and seven times as many have returned home wounded. And still: unless you understand these statistics at a human level they’re just numbers in a string of news stories. Enter James Gandolfini. As Tony Soprano’s reign as the don of cable was coming to an oh-so-clever close, the Emmy-winning actor sat down with 10 severely wounded troops and listened to their stories for his first project as a producer Alive Day Memories: Home From Iraq.

Premiering on September 9, Gandolfini’s enthralling doc is an intimate look into the harsh physical and emotional toll exacted on Iraq vets by their “Alive Day,” the day they barely escaped death on the battlefield. “The fight doesn’t stop when you get home,” Cpl. Jacob Schick explains on camera. “In our cases, it’s just begun.” Schick, a 24 year old machine gunner who served with the 1/23rd Marines, Bravo Company, met his alive day on September 20, 2004—just a month after he arrived in Iraq—when his Humvee ran over a pressurized anti-tank bomb while running a security patrol outside Al Asad.

Premiering on September 9, Gandolfini’s enthralling doc is an intimate look into the harsh physical and emotional toll exacted on Iraq vets by their “Alive Day,” the day they barely escaped death on the battlefield. “The fight doesn’t stop when you get home,” Cpl. Jacob Schick explains on camera. “In our cases, it’s just begun.” Schick, a 24 year old machine gunner who served with the 1/23rd Marines, Bravo Company, met his alive day on September 20, 2004—just a month after he arrived in Iraq—when his Humvee ran over a pressurized anti-tank bomb while running a security patrol outside Al Asad.

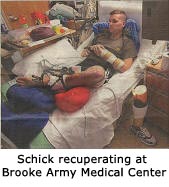

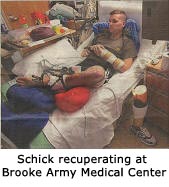

“I can’t even remember the day I arrived, I just remember the day I got hit,” he says. “My left leg was broken with compound fractures, my right leg was broken, my foot was crushed, my left arm was broken with compound fractures, and one of my bones got blown out of my arm.” Three years, two hospitals and 46 surgeries later, Schick is still fighting for his brothers-and-sisters-in-arms. His hope is that they don’t face the same hardships as he did, especially on the V.A. benefits front, when they too return home.

Your “Alive Day” came pretty quickly after you arrived in Iraq. What was going through your mind when you got hit?

I was lying in the sand. I got blown from the Hummer. It pretty much blew up right beneath me, and for some reason or another I never lost consciousness or went into shock. I remember everything except hearing the blast. When they took me to the command post, the doc started working on me, the corpsman and some other Marines were trying to dress me up the best they could, but they were having trouble stopping the bleeding out of my left leg and my left arm. I just remember they would wrap me and I’d bleed through the bandage, they’d take it off, wrap me again, just a constant process while we were waiting for the bird to get there. Everybody was just saying words of encouragement but I was pretty mad they were talking. They were just doing what Marines do. They were scared. I could tell by the look in their eyes they didn’t think I was going to make it.

I was lying in the sand. I got blown from the Hummer. It pretty much blew up right beneath me, and for some reason or another I never lost consciousness or went into shock. I remember everything except hearing the blast. When they took me to the command post, the doc started working on me, the corpsman and some other Marines were trying to dress me up the best they could, but they were having trouble stopping the bleeding out of my left leg and my left arm. I just remember they would wrap me and I’d bleed through the bandage, they’d take it off, wrap me again, just a constant process while we were waiting for the bird to get there. Everybody was just saying words of encouragement but I was pretty mad they were talking. They were just doing what Marines do. They were scared. I could tell by the look in their eyes they didn’t think I was going to make it.

Did you think you would?

Yeah, when I took my first breath after I couldn’t breathe for a couple minutes, I thought, “Done deal, I’m not dying today.” My staff sergeant came over, helped get me on the bird, kissed me on the forehead and said, “I’ll see you soon, Devil Dog.” And that was it. They took me off to Balad. I remember asking one of the guys in the flight crew, “How long?” He said 12 minutes. I started getting weak, I was bleeding out so I was pumping myself up, “Dude, you can do this, you can make it 12 more minutes.”

Was there anything about that day that seemed off to you? Did you have any bad feelings about that patrol?

I had it the day before. I just knew something bad was going to happen. I didn’t know what but I did have a bad feeling. I called my mom, my dad, my brother, my sister. Whoever I could get a hold of the night before. I just got a feeling in my gut and I just knew something was going to go down, and lo and behold, it did.

What made you want to join the military?

I played 5A Texas football. We could have beat pretty much any DII college football team out there. I could have got a scholarship to a small DII school, but I made my mind up. I’m a third-generation Marine. My grandfather was a scout sniper on Iwo Jima. My uncle was a Marine in Vietnam. I thought it’d be a great honor to serve my country and I still think it’s the best job in the world. I just think the government needs to do their part when you’re all messed up and you’re home from the war.

Where is the breakdown in the system?

It’s not the Marine Corps I have the problem with, it’s the politicians who don’t give a damn about our wounded but then they go to these yearly VFW meetings and say, “You’re the finest in the world, without you we wouldn’t be here, we wouldn’t have a job.” Whatever. Quit talking. Prove it.

Why did you agree to participate in this documentary?

I just thought it would be a good opportunity to explain my story, tell my story from a firsthand point of view and hear the story of other soldiers and Marines who got wounded over there, and how their lives have changed. I think it’s important for the American people to know how difficult it is for transition when we get home, as far as the soldiers, Marines, sailors, airmen that get severely wounded. The transition from being a fighting force to not being able to move in a hospital bed for eight or nine months is pretty rough and I think that needs to be brought to the American people’s attention. You know when we get home we get the best care in the world when we’re first home and we’re wounded and we’re in the hospital and all that, then when we get out and we separate it’s like where does all the care go. It’s like nobody gives a damn anymore.

Do you think that’s a VA problem?

Oh yeah, who doesn’t have a VA problem as a wounded person? I’d like to meet them. It’s the most laughable, inconvenient system I’ve ever been associated with in my life. I think it’s funny how the American people who enjoy their freedoms everyday will turn their cheek about it. They think just because it’s tough that it’s something that can’t be done. People have to stand up. I’m going to continue fighting the rest of my life for one thing or another. I’m considered temporarily retired. Every five years I have to get a head-to-toe physical from the VA to make sure my leg didn’t grow back.

That’s kind of absurd.

It’s ridiculous.

Is there any particular hang up on the home front that really made an impact on you?

Getting a wheelchair. I lost my right leg so I have to go and make an appointment and meet with orthotics and they have to determine what kind of wheelchair I need before I can get a wheelchair. I can’t just call and say, “Look my wheelchair is wrecked, can I bring it to you and get another one?” It’s so obvious to me now why we have so many homeless veterans. Because when you come home and you’re broke and you’re battered, missing limbs, you don’t want to have to fight for every little thing you think you’re entitled to. The last thing I want to do is fight for damn compensation for hearing loss or TBI or something. I’ve had 46 operations, I don’t want to have to go and explain myself and wait and wait and wait and go to another appointment. It’s got to change.

Did you know after you got hit that you wanted to tell your story?

I’ve told my story several times before I did the documentary just for awareness. People had a lot of questions so I talked to different groups about things. I did a lot at the Rotary Club of Tyler as a favor to my grandmother. I did some in Dallas, and in Lake Charles, Louisiana with the group that I volunteer with, American War Heroes. I’ve told it a lot.

What made you start telling it?

Honestly, it was one day in the hospital when I was in San Antonio. I don’t really remember a lot in Bethesda [at the National Naval Medical Center] because I was in and out of surgery every other day for the first month and a half. I was a bad patient; people did not like to come in my room. I was a complete and utter ass, but that was my way of fighting it. One day a nurse came in, or maybe it was an old retired Marine, and that was the first time I told my story. It hurt a lot, but it helped a lot. So I figured, “What the hell?” It was my way of dealing, I guess. I definitely didn’t want to talk to a shrink.

What did you think of the whole documentary process?

It was pretty tiring, to be honest. The best part of the whole deal was when I got to meet Sgt. Eddie Ryan, who’s a fellow Marine, a sniper who got shot in the head in Iraq. That made it all worth it for me. All the filming we had to do was worth it for me to meet Sgt. Ryan. He’s one of the most motivating, outstanding Marines I’ve ever met in my entire life. I’ll probably never meet another Marine like him.

It was pretty tiring, to be honest. The best part of the whole deal was when I got to meet Sgt. Eddie Ryan, who’s a fellow Marine, a sniper who got shot in the head in Iraq. That made it all worth it for me. All the filming we had to do was worth it for me to meet Sgt. Ryan. He’s one of the most motivating, outstanding Marines I’ve ever met in my entire life. I’ll probably never meet another Marine like him.

What did you guys talk about?

We talked about the Marines, our battle scars, our war wounds. It was just motivating to me. At the same time I freakin’ cried because on my days when I wake up and I’m depressed and bitter—because I have those days you know, I’m human—I thought I could be going through this crap like Eddie and his family. It was very humbling to meet him.

In light of what’s happened to you, would you go back?

Hell yeah I’d go back. I have brothers and sisters there who are in harm’s way and here I am getting ready to go to a frickin’ premiere for a documentary. Of course I’d go back. I just had a bad day at work.

Do you have any immediate plans for the future?

I’m getting ready to start school, I want to get a degree, I want to write a book. There’s a lot of stuff I want to do, but there’s only so much stuff I’m capable of doing. I wrote for the HBO website, wrote a couple letters to a couple senators and a few mass emails. I like it; I think it’s therapeutic. But the thing I’ve found is that I have to write about something I’m passionate about. If someone told me to start writing about the Michael Vick case you’d have to pay me a stupid amount of money, because I don’t give a damn. Anything about war-related issues, V.A., the Marine Corps—obviously stuff like that is all near and dear to me.

Did this film inspire you to get more involved with that sort of storytelling?

It’s important to me that the American people understand the sacrifices that are made, and not just by me, but by all the men and women who go over there. I’ve been treated with great respect and I’m sure most people have too, but some people haven’t and that’s a damn shame. I want them to understand that those severely wounded who come home their lives are severely changed forever. They need to understand. I can understand why it could be hard for them to go to a military hospital like Bethesda National Naval Medical Center or Brooke Army Medical Center or Walter Reed. I understand why they don’t want to go, because if they don’t see it, it’s not there. But they need to understand what prices are paid to keep these streets safe. Whether they agree with the war or not, I don’t care, that’s their prerogative, but they will support the troops. You got any kids?

No.

Well, says your friends’ kids are playing in the front yard and a car sets off an improvised explosive device. That would be shocking wouldn’t it? But they don’t have to worry about that because they live in America. We’re the freest country in the world, and yeah it’s hard to turn on the TV everyday and see something about Iraq. I know it’s hard. It sucks, but that’s reality. War is unforgiving, but it’s necessary, and as long as we can foil one of these coward’s plans that want to attack us oh well. We need to do that. If us being there keeps them from coming here and achieving what they want to achieve here, which is really mass casualties, mass fatalities. So be it. That’s what it takes. They don’t fight like men because they’re cowards. Print that in big black bold letters.

Premiering on September 9, Gandolfini’s enthralling doc is an intimate look into the harsh physical and emotional toll exacted on Iraq vets by their “Alive Day,” the day they barely escaped death on the battlefield. “The fight doesn’t stop when you get home,” Cpl. Jacob Schick explains on camera. “In our cases, it’s just begun.” Schick, a 24 year old machine gunner who served with the 1/23rd Marines, Bravo Company, met his alive day on September 20, 2004—just a month after he arrived in Iraq—when his Humvee ran over a pressurized anti-tank bomb while running a security patrol outside Al Asad.

Premiering on September 9, Gandolfini’s enthralling doc is an intimate look into the harsh physical and emotional toll exacted on Iraq vets by their “Alive Day,” the day they barely escaped death on the battlefield. “The fight doesn’t stop when you get home,” Cpl. Jacob Schick explains on camera. “In our cases, it’s just begun.” Schick, a 24 year old machine gunner who served with the 1/23rd Marines, Bravo Company, met his alive day on September 20, 2004—just a month after he arrived in Iraq—when his Humvee ran over a pressurized anti-tank bomb while running a security patrol outside Al Asad. I was lying in the sand. I got blown from the Hummer. It pretty much blew up right beneath me, and for some reason or another I never lost consciousness or went into shock. I remember everything except hearing the blast. When they took me to the command post, the doc started working on me, the corpsman and some other Marines were trying to dress me up the best they could, but they were having trouble stopping the bleeding out of my left leg and my left arm. I just remember they would wrap me and I’d bleed through the bandage, they’d take it off, wrap me again, just a constant process while we were waiting for the bird to get there. Everybody was just saying words of encouragement but I was pretty mad they were talking. They were just doing what Marines do. They were scared. I could tell by the look in their eyes they didn’t think I was going to make it.

I was lying in the sand. I got blown from the Hummer. It pretty much blew up right beneath me, and for some reason or another I never lost consciousness or went into shock. I remember everything except hearing the blast. When they took me to the command post, the doc started working on me, the corpsman and some other Marines were trying to dress me up the best they could, but they were having trouble stopping the bleeding out of my left leg and my left arm. I just remember they would wrap me and I’d bleed through the bandage, they’d take it off, wrap me again, just a constant process while we were waiting for the bird to get there. Everybody was just saying words of encouragement but I was pretty mad they were talking. They were just doing what Marines do. They were scared. I could tell by the look in their eyes they didn’t think I was going to make it. It was pretty tiring, to be honest. The best part of the whole deal was when I got to meet

It was pretty tiring, to be honest. The best part of the whole deal was when I got to meet

Send

Send  Expect sensory bombardment. Just when you’ve decided the scene is strange—maybe you’re walking around the festival and a gaggle of motorized cupcakes whizzes past, while a troupe of French maids is trying, ineffectually, to tidy up the desert with feather dusters, all in the shadow of a barn-sized rubber duck with a jazz club in its belly. Then things will probably get weirder.

Expect sensory bombardment. Just when you’ve decided the scene is strange—maybe you’re walking around the festival and a gaggle of motorized cupcakes whizzes past, while a troupe of French maids is trying, ineffectually, to tidy up the desert with feather dusters, all in the shadow of a barn-sized rubber duck with a jazz club in its belly. Then things will probably get weirder.