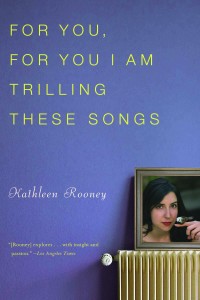

Interview: Kathleen Rooney, author of For You, For You I Am Trilling These Songs

Friday, March 5th, 2010

“Writing is a way to make sense of things that don’t make readily apparent sense.”

At age 29, Kathleen Rooney has already published two books, several books of poetry, co-created the independent Rose Metal Press, taught university writing classes, and worked as a Senate aide for 11 years. If that doesn’t seem enough, her memoir For You, For You I am Trilling These Songs came out last month from Counterpoint Press. The memoir is a collection of eleven essays that span Rooney’s journey from young adulthood to literary, slightly older young adulthood, and include references to both feminism and bikini waxes, tirades against plagiarism, third-person reflections on what it means to work for a prominent state Senator, love letters to Weldon Kees and John Berryman, and meditations on nuns and humility. Julia Halprin Jackson chatted with Rooney over the phone to get the skinny on what it means to be a young woman memoirist in 2010, and what risks writers of nonfiction take.

The format of the book is a series or collection of essays. It seems natural to ask how you choose to order them. Was it following a chronology in your life, or was it more thematic, or was that something that you had control over?

The format of the book is a series or collection of essays. It seems natural to ask how you choose to order them. Was it following a chronology in your life, or was it more thematic, or was that something that you had control over?

I tried to put the book together almost as if it was an album. Each essay can stand alone, like each song can stand alone, but also like an album you can read it all the way through or listen to the whole thing together. The basic structure was chronological: I start as a younger person and by the end I am at the oldest that I get in the book. Within that, I worked really closely with my editor, Roxie Aliaga at Counterpoint, who’s amazing, and based on her feedback on how the book was working or not working. She ended up cutting one big essay that I was sad to see go, but helped me understand it made a better book. And then, in light of that cut, we swapped a couple of the middle essays to make the narrative a little more clear. Because again, even though it is eleven separate stories that can operate by themselves, she and I both did want to make it have a bit of an arc from beginning to end.

I’m curious about the title. The title jumped out at me immediately because it’s really poetic and quite beautiful. Is there an epistolary theme throughout? Is there someone intended with the “You?”

It’s from a Walt Whitman poem called “O Democracy.” I love Walt Whitman; I think he is one of my favorite poets, and I think he’s a lot of people’s favorite poet. One of the things that I love the most about him is that he is able to write in such a broad range of emotion, but especially well in this really generous, big-hearted, ecstatic mode. I think a lot of times, people, especially people who aren’t poets themselves, think of poets as these sad, gloomy, depressive, suicidal people. Not to dismiss that stream of poetry—I love Sylvia Plath—but I think Whitman is a great example of someone who, even though he knows his country or his lover or whoever he’s talking to, whoever the “you” is, might disappoint him, he just keeps trying and keeps being generous and offering in his emotions. I like it because he’s so fearless.

On a similar note, you incorporate a lot of interesting references and quotes throughout. In “To Build a Quiet City in My Mind,” you even retrace the steps of poet Weldon Kees and visited all of his former apartments in New York City. In other essays, you reference Whitman, John Berryman, Roland Barthes, and even Plato. What was your impetus to incorporate these quotes?

It’s interesting as a personal essayist and as a memoirist to see how people react positively or negatively to the decision to incorporate a lot of other writers and a lot of quotations. In the Berryman piece or the Kees piece, there’s almost a pastiche approach, where you hear as much from these other writers as you do from me. It seems like some people really like it, and this is the effect that I’m going for—hopefully by learning about these writers, you might want to check them out, or at least find them relatable and interesting in a way that I do.

Whereas other people say it can seem like a crutch, or like I rely too heavily on them. I respect and understand both perspectives. Part of what I’m trying to do by incorporating so many other references and external things in my writing is to keep me from looking exclusively inward. I do think that the personal essay and the memoir are certainly a great opportunity for self-exploration, but you want to temper that with this ever-present sense that there is a wider world that the self is moving through. I don’t know if that succeeds, but that’s the effort.

Well, also, it’s the acknowledgement that every great writer is inspired by someone, even if it’s someone like Walt Whitman. I’m sure Walt Whitman had his people he was inspired by, too.

Another thing I thought was interesting, too: I thought the essay “I Will Catch You,” which describes your experience with student plagiarists while teaching at a small university, was particularly compelling. The Washington Post reviewer commented that this essay should be required reading for college freshmen, and I tend to agree. There is this disconnect in this particular generation between understanding what is a paraphrase and what is plagiarism, and what the consequences are, and why they’re important. What advice do you have for young writers who want to imitate writers they think are great, but still want their work to be original? What would you say to them?

I think always keep your copy of the MLA Handbook handy, and if you’re not sure how to cite, look it up. I do think, not to be too much of a police officer about it, but it’s hard to overstate how important it is to acknowledge when you are literally using someone else’s words.

As for imitation, I don’t know if it’s advice, but more of an observation: there’s this concept that Harold Bloom has, of strong misreading. I’m paraphrasing him here, but the idea is no matter how much you sit down and think, “OK I’m going to sound like Salinger, I’m going to do my best Joan Didion,” for better or worse, you’re always going to come out sounding like you. So I think, acknowledge your influences and don’t be afraid of being too derivative, but also embrace that reality that you’re never going to be who you admire. You’re going to be who you are.

One thing many readers often assume about memoir is that the writer is an older person looking back on an entire lifetime, so I find it interesting when memoirists zero in on a specific decade or era of their life. In your case, your essays all take place during your 20s. What is it about this time of life that you feel lends itself to writing memoir?

One thing many readers often assume about memoir is that the writer is an older person looking back on an entire lifetime, so I find it interesting when memoirists zero in on a specific decade or era of their life. In your case, your essays all take place during your 20s. What is it about this time of life that you feel lends itself to writing memoir?

One of the things that has been really notable about the way that the book is received is again, how it seems kind of polarizing. Some people are very much enthusiastic about saying, “Great, now we can hear more about this not-as-heavily-written-about period of life,” whereas there are other people on the other side who are like, “Oh boy, twenty-something ennui. Twenty-somethings should wait till they’re all grown up and wise before they write about it.” I guess the reason that I did want to write about it is because writing is a way to make sense of things that don’t make readily apparent sense.

I think a person’s twenties can be the most confusing, chaotic, disappointing times, and so to write about it would’ve helped me. It was almost like I didn’t have a choice. I also think that there’s a great appeal to these myths of a narrative arc: there’s this desire to think you start out young and confused and inexperienced, and then you pay your dues, you do your hard knocks, and then at the other side you come out this older, and automatically wiser, better, more talented person. I don’t know that that’s true. I think that is a myth. I think it’s valuable to hear from people at any age, just as it’s valuable to hear from people of different economic backgrounds or different countries of origin. I think it’s diversity.

Another question I have for you is about the choice to switch to third person in some of your essays. In one of your essays, you mention that your husband, who is a novelist, says offhand that if you write in third person, then your writing becomes fiction.

Yeah, that’s in “Did You Ask For a Happy Ending?” when we go to the Olympic Game Farm.

I thought that was an interesting moment, because it is a shift. It’s interesting to hear that it was an obvious choice on your part to put a little distance there, perhaps, to treat certain vignettes differently. Is that something that if you had students who were interested in writing memoir, to try writing in the third person?

Yeah, definitely. When I am teaching, one of my favorite activities to teach early on in a workshop or in a series of classes, is one on point of view. I like to do that whether the class I’m teaching is poetry or whether it’s fiction or whether it’s nonfiction. I think it’s really useful, at least as an exercise, just to open up that door. To say, OK, I’m going to write something in first person, or I’m going to write it in whatever is my natural default, which if you’re doing nonfiction, is probably nine times out of ten going to be from the “I” perspective. So, write it that way for a couple pages, and then pop it into a different one.

I’m continually surprised when I approach my own writing. Students are especially surprised when you pop something into second person from the third person; what is lost and what is gained? In the “you,” “you do this,” “you do that,” “you say this,” “you say that,” it becomes very immediate and very intense, and you get this real emotional, visceral connection to the protagonist. Whereas, if you’re not careful, it can kind of lose the big picture. If you do third person, then you get this huge, sweeping, almost dream-like in the John Gardener sense of fiction, and you see the whole landscape, and you’re kind of watching yourself do stuff. I’m certainly not going to say one person is better than another, but it’s fun to try it in different persons and see what you get.

In that same essay, “Did You Ask for a Happy Ending?”, you take an interesting storytelling approach in the way it divides the story of you visiting Olympic Game Farm with your parents into several different chunks. Each section has a self-reflective, meta-title, such as “Essay Introduction A,” “Necessary Expositional Dialogue about Setting A,” “Act 1, Version A.” What inspired this approach?

I really like writing that acknowledges itself as writing. Sometimes I want to disbelieve, or have the curtain pulled back and see how things are operating. Some of these techniques, especially in that essay, are me trying to say, “This is artificial. This is artifice. This is a presentation.” Maybe it’s more complicated than the reader might initially think.

I think part of being a writer is how you’re going to present your experience. I also think–an interesting thing that comes up when you’re reading or talking about or reviewing other people’s personal essays or creative nonfiction is who is the self? They’re presenting the self and they’re having you critique it. Is there any one true, stable self? I think I would say no—of course you’re a different person when you’re with your parents than when you’re out at a bar with your friends, than you are when you’re standing in front of a classroom teaching.

Sometimes people approach memoir with a set format because it’s viewed as a factual piece, and the writer feels he or she must write in the first person or in chronological order. That’s not necessarily true, and sometimes the most exciting approach memoir from a different perspective.

When you’re writing about a period of your life, you have a lot of material to draw from, whether it be the minutiae of daily life or major life events. How did you choose which vignettes or essays to leave in, and which ones to leave out?

As a writer not just of memoir but as a writer in general, one of my strategies is to overproduce, to just write and write and write with the understanding that you will then edit and edit and edit. Hopefully what you see, at least in my finished work, is a distillation of what I thought was hopefully the best, or the most thematically connected, episodes. I think it can be hard, too, especially when you are writing about a whole time period, you’ve got this bottomless wealth of material that you think you can include, and you have to be kind of ruthless and let a lot of it go.

You have worked for many years as an aide in a Chicago Senator’s office. Several of the vignettes in your book describe your experiences working in the office, whether it was training summer interns, helping campaign, or driving the Senator around the state. You never name the Senator in the book, but one of the essays that you wrote about in the third person plays with the motif of gender in the workplace in such a way that has provoked a mixed response. I wanted to give you an opportunity to respond to that here—how do you feel about the response you’ve gotten in regards to this essay?

That’s a complicated situation. I was dismissed from my job as a result of publishing this book, and I think I’m very sad and very disappointed that that happened, because up until the very, very end—I was dismissed earlier this month—they were nothing but supportive. I was on a temporary part-time schedule to write a novel, with the understanding that it was a novel that was going to draw largely on my experiences in that workplace. My coworkers and supervisors bought my books, came to my readings. So I think what happened there was that it was a disconnect with the Chicago office, which was very supportive, and the D.C. office didn’t maybe realize how extensive or serious my writing career was, and when they found out, and when they found out in a way that they found embarrassing for them, they acted to remove the threat, which was me. It’s not what I would’ve wanted to happen, because I had that job over the course of 11 years, but I’m trying to see it as an opportunity to go do something that will be a little more intellectually free.

A lot of people say, “Knowing what you know now, would you do it again?” And I guess I probably would.

I know you are an active reader, and in your book you often mention reading on the Chicago El trains. What are you reading these days?

I really like reading young-adult literature and kids’ literature, so I’m finally getting around to reading Phillip Pullman. I’m reading The Golden Compass right now and working my way through all those. I also just finished a really, really wonderful novel—very short novel, Cut Away by Katherine Kirkwood. I’m actually reviewing it for Bitch Magazine. It’s this novel told from three different protagonists’ perspectives, and it focuses on gender and plastic surgery and identity, which could have been a very heavy-handed, polemic book, but instead Kirkwood does this beautiful Lynchian, dreamy, very human thing with the book, and I just couldn’t put it down.

What writing projects are you working on now?

I’m actually in the middle of finishing the first draft of what I hope will be my first novel. Also, I’ve been doing this collaborative project for the past four years. I co-write these poems with my friend, the author Elisa Gabbert. She lives in Boston, and I live in Chicago, but through the magical powers of the Internet we are able to communicate all day long over Gmail. She’ll send a line, I’ll send a line, and with this form of experimentation we’ll come up with the form that we use. It might be a real historic form, like a sonnet, or it might be something we just made up ourselves. By using these rules, we actually find ourselves being more creative than if we wrote whatever we felt like with no restrictions.

And finally, Kathleen Rooney, what’s your Six-Word Memoir?

Out but not down. Second act.

++++

BUY a copy of For You, For You I Am Trilling These Songs

VISIT Kathleen Rooney’s website to learn more about her other books and poetry

CHECK OUT Rose Metal Press, the independent press Kathleen Rooney co-created

I would like to 2nd that emotion that the essay on plagiarism should be required. I have already shared it with 2 h.s. English teachers and one college professors, who upon reading it, are of like mind.

I think this, not because of the “bad college students, cheating is bad, and so are you!” type of message that comes across in other works around this theme, but because Rooney’s self/character is so know-able (err…) in that essay as a fellow human among her students, who will see the very complex, very real troubles that the horrible decision to cheat can create.

And, oh yeah, how obviousemente it is.

Good to hear from you Mike. I always know extlcay what to write to get you to pipe up, right? Reasonable people can disagree on these rankings, but Syracuse did just lose AT HOME to Pitt by DOUBLE DIGITS. I understand the Kansas-Cornell analogy by we all know Kansas would beat Cornell 9 out of 10 times. That’s the definition of a fluke. Can we say that about Pitt-Cuse? I don’t think so. Let me see more and then I will adjust accordingly. As for West Virginia and Villanova, I’ve had them 1-2 in that order since October and I see no reason to change that right now. Nova losing to Temple in one of those crazy Big 5 games (where upsets are commonplace) doesn’t upset the apple cart in my mind. Again, it’ll all play out. I actually enjoyed Boeheim’s postgame after Seton Hall, even his potshot at the media about OOC schedule strength (at least the quotes were interesting and usable). Much better than the normal blah-blah-blah you get from a lot of the other guys. Bitter, the point about last year’s Big East is how it was the deepest league ever. Obviously no league was better at the top than those mid-80s Big Easts. If it makes you feel better the next time it comes up I will put an asterisk and a footnote making this distinction. Piratefocus,I’ve been beating the drums for Fero Hall as you know, but he is way too small to play center in the Big East. Have you seen the size of the postmen on the other teams? Big John is a space-eater and is useful in short spurts (alas, his knees have robbed him of the rest). Fero has to beef up big-time before he can hold his own at center for any reasonable lengths.

What a nice interview! I want to check her essays now. I might even share this collection https://pro-academic-writers.com/blog/types-of-academic-writing on my website.

You really should post your interview https://www.bestessays-uk.org/case-study here. I would love to see more content from you because you are good at it.

mnj

We provide proper guidance for , for structure, research, topic help and editing/proofreading.

Good info. Lucky me I recently found your site by accident (stumbleupon). I have book-marked it for later!