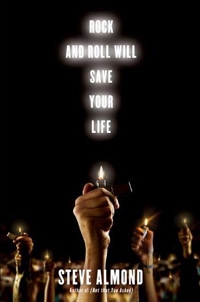

Interview: Steve Almond, Author of Rock and Roll Will Save Your Life

Monday, May 3rd, 2010

“The best songwriters are really fantastic storytellers; they only have three or four verses and a chorus to get it across. Listening to songs made me realize: it’s my job to get to the heart of this thing as quickly as I can.”

Steve Almond is a Drooling Fanatic, a breed he describes as “wannabes, geeks, professional worshippers, the sort of guys and dolls who walk around with songs ringing in [their] ears at all hours.” After a few years as a music critic in El Paso, Almond decided, with the help of a revelatory moment at an MC Hammer concert, to leave that profession behind. All while attending concerts and collecting an absurd amount of music, he moved on to teach creative writing and release several books, both fiction and non-fiction, including a self-published collection of short stories, This Won’t Take But a Minute, Honey.

His latest book, Rock and Roll Will Save Your Life, is a trip through Almond’s life via the musicians he loves and over whom he drools. While it would be easy for Almond to just write verbose profiles on his favorite musicians—the bulk of early drafts, he says—the book, in the end, reveals more about the emotions of the author, through honest and intimate personal stories, than the art of the musicians themselves. From multiple exegeses of both banal and brilliant song lyrics to accounts of Almond stalking his favorite musicians, Rock and Roll is a hilarious and sincere memoir detailing the emotional support music gives not only to Almond’s life and in those nearest to him, but to the lives of Drooling Fanatics everywhere. He spoke with SMITH from his home in Arlington, MA, just outside Boston.

First off, your book is hilarious. I was laughing out loud in public, on the trains. You’re very funny.

First off, your book is hilarious. I was laughing out loud in public, on the trains. You’re very funny.

You know, funny is the way you deal with the world and especially the way you deal with a certain kind of unhappiness, for the most part. People tend to see comedy and tragedy as somehow separate realms, and the fact of the matter is that they are different sides of the same coin, almost inevitably. In my own particular family there was a lot of antagonism, a lot of competition, a lot of sense of deprivation. At a certain point I realized that I was probably better off admitting what a mess I am than the energy that it took to cover that up—it’s exhausting, depleting.

You’re book drives the point home that music is a way to access emotions that are otherwise inaccessible, emotions that you beautifully write about. How does your experience of listening to music play into your writing process? Do you listen to music while you’re writing?

Oh yeah, it’s on all the time, especially in those years that I was sitting around in my underwear in Somerville, feeling very deeply my young artist angst. These songwriters were the people who taught me the essential lesson, and it took awhile for it to sink in, which is: it’s your job to be emotionally honest and to grant yourself that right.

The best songwriters—and these are the ones that end up sticking around for me, in heavy rotation for years, and then I get all obsessed and drooly over—are really fantastic storytellers; they only have three or four verses and a chorus to get it across. Listening to songs made me realize: it’s my job to get to the heart of this thing as quickly as I can.

What I’m always writing toward are moments of lyric intensity, where the character is in a very complicated moment or emotional situation and rather than speed through it or away from it, you slow down; then there’s this compression of sensual and psychological details where, in an effort to capture the truth of that character’s feeling, lives the language in that lyric register, and it starts to become more poetic. The rhythm and melody, the euphony of language is released onto the page. Not because you’re consciously trying to write well, but because you are trying to express this complicated place that this character is in, where you’ve brought this character. Or maybe this character has brought you, if you’re lucky.

You’ve touched on something, a quote that I’ve pulled from the book, that you’re thinking about “the broader relationship between language and music, how melody and rhythm can animate dead language.” And I feel you torn two ways: as a Drooling Fanatic that’s an awesome thing, and as a writer that kind of sucks.

You’ve touched on something, a quote that I’ve pulled from the book, that you’re thinking about “the broader relationship between language and music, how melody and rhythm can animate dead language.” And I feel you torn two ways: as a Drooling Fanatic that’s an awesome thing, and as a writer that kind of sucks.

I was just dancing, having a little family dance party with my kids and the song that came on the radio was “Don’t Stop Believing” by Journey, which I know you never will stop believing. I was sitting there thinking, Don’t stop believing, da da da da—it’s like a Pepsi ad but, you know, my kids and I were totally feeling it. And this is the thing: the musicians who bother to write really beautiful stories and really know how to lay their characters bare, god bless them, because they’re doing us a really big fat favor and, frankly, they don’t have to. You know [the chapter in the book], Reluctant Exegesis: “(I Bless the Rains Down in) Africa”—everybody knows what a cheesy, crazy, imperialist piece of Muzac that is, and yet they fucking love it. They hate themselves for loving it, but they still love it, and that’s the blessing of music.

How do you think you can bring melody and rhythm and aspects of music into your writing when you don’t have a musical background?

When you’re really loose and not self-conscious the musicality of language will emerge if you’re having enough fun, if you’re really dancing in the right way at the keyboard. And I think that happens with a special intensity when you reach these moments that are very emotionally and psychologically complicated and you throw down in the midst of them. Whether it’s Reverend Hightower in Light in August or the last paragraph of The Dead, whatever it is, there are these moments where you can tell that the writer is singing.

You write a lot in the book about your past as a music critic, and your disdain for music criticism. Most recently you wrote about music criticism in an Op-Ed for the Boston Globe. Are the music critic and the book critic related for you? Or any art critic for that matter?

Of course they are, and I say this as somebody who reviews a lot of books, too. It’s the critical impulse, which in its best moment is an attempt to understand what a piece of art is articulating and how it arises from the culture and what it says about the culture we’re living in. It also tells us about the pleasures and disappointments that we might experience in a given piece of art, and both of those missions are totally unassailable and awesome, and they are why I make good criticism and they are why I enjoy reading good criticism.

But how many reviews of music or books or whatever it is that you’ve read do that versus the ones where you know that there is basically some envious, bitter dude or dudette expressing their own sensibilities. The greatest piece of writing about this is Tobias Wolff’s Bullet in the Brain. I think that the vast majority of stuff that I read, whether it’s book or music criticism, especially these days, falls into this category of literary punditry. The reason I’m a Drooling Fanatic and not a critic is because I believe that you can’t tell someone their ears are wrong, you certainly can’t tell them their heart is wrong.

You kind of do both in the book: you take witty, sarcastic punches and then go back on yourself, and say, But it’s okay, as long as people are feeling something. It seems like you’re really balancing your music critic voice with your intense empathy.

I don’t mean that people shouldn’t have a critical faculty. I don’t mean that we shouldn’t draw distinctions between the kind of work that Joe Henry is trying to do as a lyricist and artist and the kind of work that Toto is doing. All I’m saying, in the end, is they’re both trying, and if Joe Henry is more successful to me [then] I want to articulate why because I think the culture’s better off when it’s engaged in deep acts of imagination.

Given all your writing on embarrassing shenanigans with rock stars and your reflections on those shenanigans for everyone to read, do you feel vulnerable? It’s your life on display. Do you consider Rock and Roll to be your memoir?

The book is for people to read and hopefully experience, but also to think about their relationship to music and all this stuff that I obsess over. You can tell talking with me, I think a lot about, Are we going to survive or are my kids going to survive? It’s already getting nasty and mean, there are already people who want to take shots at our democratically elected president—bullet shots, with guns. So if that’s happening and we still have 99 percent of our wealth and plenty, then what’s going to happen when it’s not easy for us to get fuel anymore or clean potable water? I worry about that stuff a lot.

As for talking about my life, of course, it’s about my life. A lot of what I was trying to do was just the same thing I did in Candyfreak—let me just tell this story through what I know best and what I care about the most. In the end, as I try to suggest through the book, it’s really hard to write about music; it’s this other language and you can’t do it really with words. But what you can do is write about your feelings around it and the experiences around music, and that’s how I think most people think of songs anyway.

What are some books that have influenced your writing? I know what you’re listening to via your free playlist, which is awesome.

In high school and in college when I was thinking, I’m just going to be a reporter, one of the few kinds of books I was reading were Vonnegut’s books. They were sending a very basic message that had a lot to do with what I’ve talked about: dealing with tragedy with a comic approach to it rather than trying to be serious and angsty. What’s amazing about Vonnegut is that he writes about the biggest issues facing the species in a way that’s not just funny but rescuing in its humor, and he also is very straightforward. There’s no pretense in his writing at all; it’s very conversational. He’s like Twain—the central character in the middle of his work is him, his voice, that sense of this benevolent god who’s looking down upon his creations with unlimited love—that’s totally crucial to me.

And certainly, I’m thinking about Barry Hannah, who died recently. In grad school, reading his stories in Airships was like, I get it: you’ve got to write about people who are right at the end of their tether, who are in real trouble. You’ve got to allow yourself and them and everybody to be crazy and crazily honest. I found a book, Stoner, in grad school as well, that I’ve been trying to press into people’s hands ever since. It’s just one of those books that is perfectly written—there isn’t an extra word. It’s devastating, there are no fancy histrionics, he stays so close to his characters and their emotional lives and it is absolutely devastating.

The book feels like one long, complicated love letter to the tragic love of your life, who you know you will love forever but only through heartache and pain. And then you turn it all around at the end of the book, seemingly content in the tragedy of it all.

[Laughs] I think most people in this era are living under a cloud of disappointment that they didn’t get to be the creative artist that they wanted to be. Because I think most people in the end really do want to express who they are and be known by the world and be loved for that. And very few people get to do that. It’s true that at a certain point, the dream of being an artist or a rock star is very much about wanting a certain kind of love, and when you have kids, especially late in life and you can recognize how delightful that is and how consuming it is—you know, it’s not the same as being a rock star, but it’s emotionally way more important. I’m not going to suggest that it isn’t an ongoing tragedy every time I go to see a concert, I think, Oh fuck man, why am I stuck just being a writer? But you know, after awhile you just manage your disappointment about that stuff.

I read that this book was part of a duo, are you working on something currently that’s related to Rock and Roll Will Save Your Life or something different?

No. The next thing that’s going to be out there—unless I self-publish something else, which you shouldn’t put past me because I think that’s where it’s all moving. The next thing that’s going to come out that I’m not going to put out myself is a book of short stories—yay! Back to my first love, called God Bless America. It is coming out late next year and I could not be more fucking psyched about it.

Finally, Steve Almond, what’s your Six-Word-Memoir?

Got baked. Rawked out. Wrote book.

+++

VISIT Steve Almond’s website.

BUY Rock and Roll Will Save Your Life.

LISTEN to Almond’s “Bitchin’ Soundtrack.”

READ an excerpt of Rock and Roll on The Rumpus.

My favorite phrase is, “then there’s this compression of sensual and psychological details where, in an effort to capture the truth of that character’s feeling, lives the language in that lyric register”. I like your perspective.

[...] Save Your Life (official website) The Morning News interview (2010) Vanity Fair interview (2010) Smith Mag interview (2010) The Nervous Breakdown self-interview (2010) The Rumpus interview (2010) Largehearted Boy [...]

I will definitely post this interview https://resumecvwriter.com/blog/how-to-list-freelance-work-on-resume here. People should read it.

I love rock’n'roll. If you are using the soundcloud platform to promote your music to the masses, then I advise you to go here https://promosoundgroup.net/collection/buy-music-promotion/buy-soundcloud-promotion/ and consider using the help of organic promotion of your music. This will help you quickly achieve popularity in the music field and possibly become a world famous star.