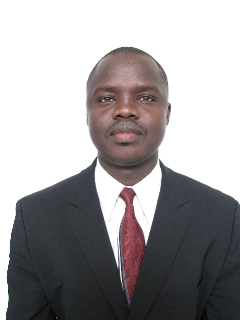

Interview: Valentino Achak Deng, Dave Eggers’ Real-Life Character in What is the What

Friday, December 11th, 2009

“When you’re going through memories like that, you detach yourself. You become a researcher of your own life. That’s basically what it was; I became a researcher of my own life.”

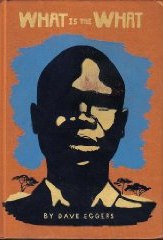

A survivor of a devastating, decades-long civil war in his native Sudan, Valentino Achak Deng now uses his voice to advocate for his people. He partnered with author Dave Eggers to create What is the What, an autobiography that details Valentino’s journey as one of the Lost Boys of Sudan, walking for weeks across dangerous open desert to escape the violence of war, as well as his resettlement in multiple refugee camps and later in the U.S.

Valentino speaks publically about the delicate peace agreement in southern Sudan and the vital support that national governments and grassroots movements can provide to avoid future violence. He has also returned to his village of Marial Bai to initiate the hands-on rebuilding process. His nonprofit organization, the Valentino Achak Deng Foundation, opened the region’s first school this May and continues to develop educational and community resources there.

I had the chance to speak with him about the process of turning his life story–the story of millions of Sudanese who experienced the atrocities of civil war–into a bestselling book and about rebuilding his country one village at a time.

So, your current speaking tours and the book and everything came about because you got into public speaking. How did you become a public speaker?

It started way back in the camps. I was a youth leader; I headed a program called Youth and Culture Program at Kakuma Refugee Camp. We had programs starting from Debating Club, Drama Club, and we had cultural troupes where we encouraged youth from different regions to keep as much of their cultural traditions as they could. And of course I was an actor in the camps. They choreographed for us, skits and role-plays, where we basically dramatized issues in our communities. And all of this has a lot to do with speaking and leadership. I used to be in charge of organizing the Refugee Days for the entire camp. I would be the Master of Ceremony in most cases.

Oh wow. And there were a lot of people there?

There were a lot of people. They were attended by thousands, sometimes more than one hundred thousand people. So that is how I got into the public arena.

And when you got older, you started to speak about different things?

Yes. When I was at the camps, it was basically about issues that affected our refugee community at the camps—things that we needed to learn so that we could take care of ourselves. But then when I came to the U.S., of course it took a different turn. I realized that the war that was going on in my country needed advocacy. Fewer people were speaking about it in the U.S, and I got a call from Mary Williams, who headed the Lost Boys Foundation. She requested me to do public speaking for the agency, to raise funds. That was the objective of the Foundation; my objective was to advocate for my people. And it was at that time that the U.N. reported that over 2.5 million people had been killed during the war and over 4 million had been internally displaced. I could not keep quiet about that.

Do you feel like it’s made a difference here when you talk about what you’ve experienced?

Yeah—it’s not only about what I have experienced but also about what millions of people and families have experienced. That’s how I look at it. I don’t look at myself as a victim because I have been able to manage to escape from all of that horror.

Is it hard for you to get up in front of people and talk about what you saw and the things you experienced during the war?

Is it hard for you to get up in front of people and talk about what you saw and the things you experienced during the war?

No, what I went through happened more than ten years ago. At the camps, nothing was happening horrible. We were just staying there. I was enjoying learning new languages and new cultures. So it was a good life. So it isn’t too hard to speak about war. The things that I saw, they happened in the eighties. I left Sudan in 1992, and I didn’t go back during the wartime. And when I left Sudan, I was young. So the age factor helped me to transition out of that.

So it’s easier now that so much time has passed since you actually experienced the war, and because you had a good life in the camps?

Just imagine John McCain—the Vietnam War. He can talk about it now, right? There are some times when I sit and remember some instances that I had to witness, right. And then I think, “This is wrong. This should not have happened to this young mother or this should not have happened to that child. Why were they killed?” But then I say, “It’s war. War has no order; it’s destructive. War is systematically destructive.”

That’s true.

It’s true, and I have to accept it. But what is the best I can do is to advocate and inform people so that atrocities such as the ones that were happening in Sudan cannot happen again in Sudan or elsewhere.

Is that why you decided to write an autobiography?

That is, yeah, that is one of the reasons I decided to do it. I could not just blend into a peaceful society and enjoy life and pretend like nothing is happening.

So the public speaking was going well and you were getting some people’s attention and hopefully making a difference in that way and you decided that you wanted to do more, and that’s how the book came about?

I wanted to do more, and I asked Mary Williams about connecting me with a writer, so we enlisted the help of Dave Eggers. I wanted to tell the story structurally so that people would understand it.

It does seem very elaborate, and people have called it “epic.” And I know it took, what, about three years to finish?

Yes, more than that.

What was that process like for you?

What was that process like for you?

I had to work very hard. I had to press myself to remember, to recall, vivid memories. I had to put people I know back into the memory and see them bleeding. I had to see this mother, young mother, killed, and her small infant trying to breastfeed on her dead mother and nobody’s helping her and she’s crying. I had to imagine my village being run over by horseback fighters and pillagers, and I had to imagine my family there, and I had to imagine myself there as a child, vulnerable, nobody’s helping me. And so it’s hard. It’s difficult to go through those memories, but I was determined to tell the story. Many times I would stay up at night and type—type anything I could remember.

It seems like you remembered a lot, and I see it being a painful thing to go back and try to remember so many details.

Yes, it’s painful, but as I told you before, when you’re going through memories like that, you detach yourself. You become a researcher of your own life. That’s basically what it was; I became a researcher of my own life.

How was it working with Dave Eggers on the book?

He was nice. He would ask questions all the time. Short questions, long questions. When did this happen? How did that happen? What can you remember about this event? Any details? So it was like working with a coach, right? Someone to say, “Ok, throw the ball this way. Stand this way. Run this way.” So that’s how it was. Actually, it was interesting, you know, researching my own life and having someone helping me say, “Oh, this happened. Put it in,” or, “That did not happen. Chop!” There was a way; there was a cause. There was a way in and there was a way out. And then these are the details. It was easier, actually; if I were alone, maybe I would have taken for granted some of the details.

So, now the book is a bestseller. What do you think about having so many people reading about your life?

That is what I wanted. And it’s not about my life; it’s informing about details of certain events that happened without our knowledge.

So a lot of people know that these things happened, the general historical events, but you try to make it personal so that people understand.

I use my story as an individual and then allow that to be something that people can connect with, that people can identify with. You read it and you think, “Ah, this happened in Sudan, and this one person went through this.” And through myself, then the readers identify with the cause itself.

I think that’s true. And so now you’ve gone back and started to rebuild in Sudan. Do you see a lot of places in Sudan that were burned down and completely destroyed, do you see them coming back to life?

Yep, yep, there is a lot happening. Thousands of people have returned to their villages and their homes; millions of families have been reunited in the last four or five years. But there is a challenge—a challenge for development, a financial challenge. But the challenges are bearable. People are excited. You can see children playing soccer and children returning to school, and there is a lot happening. I like that. That was not happening during war. People were running. Now people have returned home and are looking for a place for schools to send their children.

The Valentino Achak Deng foundation is currently raising funds to build on-campus dormitories for girls, which will help allow them access to education.

What is it like for you to go back and be involved in that yourself?

I like it. I’m being productive and I’m helping change lives and bring

back hope. We’ve built a school that opened this year. Thousands of people applied to attend our school in May. We have enrolled about one hundred students in May of this year. But we are challenged by the idea of girls going to school. Very few females are allowed to go to school. They are the ones who are expected to fetch firewood for their families and fetch water for their families, and cook, and care for their younger siblings. I don’t think that’s a conducive environment for females to learn. That’s why I have decided to raise funds to build dormitories so our girl students can stay on campus. And in fact I want more than 50 percent of our student population to be female students. So it is nice to be back and seeing myself rebuilding the country.

It’s interesting to me that you’re making a difference in so many different ways. Here, in the U.S., it’s a sort-of broader scale, where you talk to people and you have this book so that people know what happened and what’s still happening, and what still needs to be done. And you can also go back to your village and be involved in a very hands-on sort of way, rebuilding the school and helping improve the community yourself.

It is exciting, and thank you for acknowledging that. You know many people who have purchased and read What is the What have not disconnected. Many people have read the book and they ask, “What is happening to Valentino? What is Valentino doing?” And many of them have actually contributed financially. That’s how we are building, how we have managed to build a school in Sudan; we get private donations, private contributions. Most of them are the readers of What is the What who are excited to support the cause. That is a blessing and I must extend that blessing where it is most needed. That’s my inspiration.

So your inspiration is getting help back to the people in Sudan who still need it.

Yes. And it’s like I always say, it’s not about the man Valentino, but what we can do to help improve our global community.

That’s a very big task.

It’s a big task, and I will do it one village at a time, one school at a time. I will take a smaller project like our project and take it to a smaller, remote area and make a difference there, and see the impact we have made all together. And we will move to the next village.

Do you have other plans for rebuilding and for the future?

Yes, one village at a time. And we don’t only do schools; we do community development projects. We work with local women, young and old. We work with local youth. We work with local leaders and offer leadership training and environmental conservation training. We work with the teachers who are not only teaching, but teaching the teachers—master teachers.

And finally, Valentino Achak Deng, what’s your Six-Word Memoir?

Always have hope & keep the faith.

++++

READ a sample chapter of What is the What.

VISIT the Valentino Achak Deng Foundation’s website to learn more about Sudan and how you can help.

BUY a copy of What is the What.

[...] his experiences. Earlier this year, Deng sat down with SMITH’s Miranda Martin, where he had more than six words to say about his emigration from Sudan and his efforts to rebuild what has been destroyed [...]

Your willingness to tell the story of Sudan and all the terrible hardships is moving and commendable. Thank you. I am hoping you have also raised great awareness of the less than honorable treatment you and so many others - mentioned and not - received in the United States. For that I am ashamed of my country. As you have begun to make change in your nation, may we in America also make changes to enhance the lives of those who come here.

I have been involved with the Valentino Achak Deng foundation for several years. My donation are small because I am almost 80 years old, - a retired epidemiologist and Public Health officer who donates to many causes - but not being American-born and, having grown up in Geneva (Red Cros , UNs), I had many and easy contacts with Africans there and from the minute I arrived in the US. My best friend, until her death a few years ago, was another epidemiologist, Jamaican educated in London and widowed from a Nigerian officer who died in the Biaffran wars.

May God stay with you Valentino, you are a good man.

I admire your toughness and resolution to do well. You are so charitable with your time and also sources.

The way you structured the message was both rational and also convincing.

You have a way of making difficult tasks appear simple. You are an remarkable buddy!

Your wit and humor brighten my day. Your determination is motivating!

Amazing is an all-in-one life management tool that will make your life much easier than ever before.

Breathing in and out numerous times a day enhances your life tremendously.

Extraordinary is everything you need to modify your frame of mind.

You offered visitors with the essential expertise and also truths in order to make their own educated decisions.