Interview: Rachel Shukert, author of Everything Is Going to Be Great: An Underfunded and Overexposed European Grand Tour

Tuesday, August 3rd, 2010

“We need to start reinventing the memoir, like the novel, so that it’s its own medium, not just something novelists write when they don’t have an idea for a novel. We need to interrogate the form, as pretentious as that sounds. It’ll no longer be the dentistry of the literary world!”

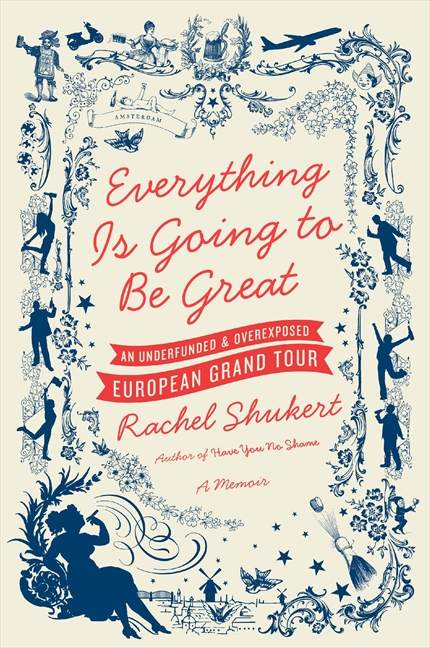

There are tens of thousands of young, hip, dirty-mouthed, pop-culture-saturated writers out there (meaning in Brooklyn). Many of you are even named Rachel. Rachel Shukert’s Everything is Going to Be Great: An Underfunded and Overexposed European Grand Tour is the book you want to write. Just recount all the crazy shit that happened after college, when you were poor, drunk, and horny, then throw in the year you traveled and lived in Europe. Comedy, cross-cultural insights, and wise life lessons will flow from your fingers. Before you know it, Diablo Cody and Gary Shteyngart (”If you read only one memoir by a disaffected, urban, 20-something Jewish girl this year, make it this one”) are blurbing you.

Before trying to write this book, you—and hell, everyone—should read this book. It is Shukert’s memoir of her life between 2003 and 2005, when, after getting a theater degree from NYU, she goes to Vienna to play a tiny, unpaid role in an experimental theater piece. After the play closes, she decides to live in Amsterdam.

While still in Vienna, she dates Berthold, a middle-aged photographer. One day, Shukert tells Berthold about an anti-Semitic remark made by the owner of the neighborhood sausage stand she frequents for late-night snacks. Berthold is appalled. Shukert writes:

“‘Whatever,’ I said, ‘I mean…All he said is that I look Jewish.’” “No.” Berthold placed his hand over mine and gazed deeply into my eyes. “No. You are beautiful.”

Like countless moments in the book, it induces explosive cackles. It also captures perfectly how contemporary Europeans’ posthistorical cosmopolitanism, so sincere and sacred, is often no match for old tribalisms. Finally, it hits a more poignant note of how her adventures in Europe add new meaning to Shukert’s Jewish heritage, a theme that culminates nicely in the book’s happy ending, when she meets and marries her husband, Ben. Funny, insightful, moving—the memoirist’s Molotov cocktail.

How do you write this way? For starters, you need to be a hot mess and a cool craftswoman. Shukert told me how she does it when we met last week.

Were you always funny?

Were you always funny?

When I was young, I started noticing that people would laugh when I was saying something serious. At NYU I got sick of doing the same monologues over and over again, so I started writing my own scenes and pretending they were by real playwrights. They were these absurd things, and people laughed. I got a grasp of what’s funny: timing, structure, building to peaks. That sensibility remained when I started writing prose.

And specificity, as when you describe one of your many unpleasant post-college living situations: “[my roommates] found it perfectly fine to pee in the kitchen sink or hoard their menstrual blood for use as plant fertilizer.”

It’s my natural way of phrasing: formality and vulgarity played off each other. This is influenced by Brits with a naughty streak: Martin Amis, P.G. Wodehouse, and Morrissey—his overdramatized emotion that’s not insincere but is aware that it’s heightened and crazy. I also love the Adrian Mole books by Sue Townsend. My publisher, HarperCollins, is reissuing them, and they asked me to write the afterword. I wept.

How else does your theater background inform your writing?

As an actor, I learned how to identify characters succinctly: What should I highlight that describes the character the most? That’s helpful. Being inside a scene gave me a sense of the rises and falls, the natural arcs. How a set piece is set up, with background characters that play off the main ones. With a book like this, I can put in all the details, in words, that you can’t if you’re writing a script. I like that.

I know a lot of actors who are good writers; there’s a lot of overlap.

The book isn’t just funny; there are moments of sentiment. How did you approach blending and shifting tones?

My whole philosophy is that you shouldn’t have to try to make something funny or tender. I’m not writing jokes; everything is built out of how I describe things anyway. You don’t have to put a soundtrack to it. And you shouldn’t underestimate the power of a cut, like in a movie.

You tell the story of how during high school in Omaha you got fired from a job at a coffee shop for playing your Sweeney Todd CD instead of the Grateful Dead. You did musical theater?

Lots. I’m Rachel Shukert, and I love musical theater!

Hi, Rachel.

Exactly. I always took a lot of pleasure from memorizing words. Patter songs by Gilbert and Sullivan, Cole Porter.

Your book does use a large vocabulary.

Your book does use a large vocabulary.

Because of those songs, I became fascinated by how English has so many words that mean the same thing but with a slightly different feeling or tone shading. When I was a small child, it was another clue to the nuances of language.

Word choice is so important to comedy. Orwell had a big influence on this book, especially his essays on India. One of his rules for writing is: never describe something how you’ve heard it described before. Lots of authors—especially of memoirs—break this rule. You get so wrapped up in telling your own story you lose track of the style.

It seems like the market doesn’t value books that are carefully written. Everyone’s into blogs, which are all about volume. It takes me a long time to write. I get so fussy. I could never write for a model like Gawker where you have to cope with this constant turnover, and I’ve never had a personal blog. Plus, I don’t like writing and not getting paid for it.

How was this book edited?

It took a lot more editing than other things I’ve done. It’s longer, with so many threads that needed connecting and balancing. When I turned in the first draft, I didn’t feel like I’d nailed it. My editor was like, “I mean, yeah, we’ll publish this…” [mimicking her unimpressed, rising tone]. I threw out a lot.

It’s very humbling. I used to get defensive or say, “I’m not talented!” Now I know that editing is where the skill is. You don’t have anything until you edit it. If you take a cake out of the oven 20 minutes early, it may taste good, but it’s not cake.

You played with the structure of the book, for instance adding sidebars: Are You About to Be Sex-Trafficked? A Checklist; Where the Fuck Am I? A Guide to Dutch Street Names…

I feel like there’s a glut of memoirs. We need to start reinventing it, like the novel, so that it’s its own medium, not just something novelists write when they don’t have an idea for a novel. We need to interrogate the form, as pretentious as that sounds. It’ll no longer be the dentistry of the literary world!

The sidebars: I love guidebooks, especially those “Did You Know?” boxes that, alongside B & B listings in Andalusía, tell you the history of bullfighting. It’s rich and exciting. At the same time, I was satirizing those contrived travel-magazine articles that claim to show you how you can have the same experience as the narrator of A Year in Provence or something. [The sidebars] were so fun to write, plus they were a way to include things that were funny but I couldn’t figure out how to work into the main narrative.

You also get meta, as in the penultimate sidebar: How to End This Book.

Another example of reinventing the form, and a reference to movies and TV—that’s how we mentally approach anything these days, it seems. Plus, memoir is inherently meta; it inherently breaks the fourth wall. There are two yous, the one writing and the character on the page. It’s inherently Brechtian.

This book combines memoir and travel writing—your establishing shot of Amsterdam is a stellar example of the latter. How did you approach this fusion? Any models? Things you wanted to avoid?

My models were novelists who set their books abroad: Rebecca West in the Balkans, Fitzgerald, Paul Bowles. I wanted to avoid a gap I saw in other memoirs set abroad. They either sacrificed the story for lifestyle-magazine scene-dressing or told the story ignoring where they were. The two inform each other; where you are makes you learn something about yourself and your inner life makes you see your surroundings in a particular way.

Talk about feminism. Your writing is strong, funny, and brave, and you also admit to and laugh at your own girliness.

I can’t subject writing to an agenda; I just have to write what it is. Ever since I was born, I’ve never given a shit what people thought of me—often to my detriment. One shitty thing is that no one accuses a man of “oversharing.” I think, as long as you’re entertaining and not letting yourself off easy, it’s O.K. I’m not defensive about the “chick lit” label; I want people to read my book, however that happens.

To me, feminism is being as fully human as men—strengths and foibles. Treating yourself that way is an inherently feminist act.

You liken the opening of an uncircumcised foreskin to “a wrinkly Cheerio, or maybe a hemorrhoid cushion for a dollhouse.” Do you have to sweat for your similes or do they just come?

They just come. All writers have some gift. Mine is for wild comparisons that describe something exactly.

That simile was in a humorous vein, but your gift extends to serious moments, suggesting a bona fide high prose style. Do you want to do more “serious” writing?

I’m starting to. I want to do a novel with funny parts but that’s not all it is. But it’s a shame that funny means “unserious.” There was a period a while back when I wrote a lot of poetry. It’s a good exercise for one’s descriptive ability, for making descriptions that feel inevitable.

Any other projects in the works?

I sold a YA [young adult] series that I may write under a different name. I’m excited; it’s a nice change of pace—third person!

Finally, Rachel Shukert, what’s your Six-Word Memoir?

Let me get back to you.

Edward Lovett is a writer, tutor, and jazz crooner. He lives in Brooklyn.

+++

BUY Everything is Going to Be Great.

VISIT Rachel Shukert’s website.

FOLLOW Rachel Shukert on Twitter.

[...] Links: The interview that sold me on [...]

[...] “twisted” and “hilariously unpredictable.” Recently, she talked to Smith Magazine about her writing style and authorial role models: My natural way of phrasing: formality and vulgarity played off each other. This is influenced by [...]

Youre so cool! I dont suppose Ive read something like this before. So nice to search out anyone with some authentic thoughts on this subject. realy thank you for beginning this up. this website is one thing that’s needed on the net, somebody with a bit of originality. helpful job for bringing one thing new to the internet!

Hey guys!

Hey! I’ve some awesome news for you! When your deadline is coming and you need to write some essays, you can use our super-professional online service. It’s really suitable when you can choose the appropriate topic for your eessay and get completed assignments. So, click on this https://jetwriting.com/ website and discover this info wright here!

https://studyjumper.com/blog/top-research-essay-topics check it

We always try to give you the best information and discounts. ??? ??? Today is full of even more special benefits. Click right now.