Excerpt: The Mercy Papers by Robin Romm

Tuesday, January 13th, 2009

“This only makes me angrier—that we’ve all been placed at the mercy of her disease, that it’s trapped us in this house, warping even our arguments. It’s not an apology she’s giving me, it’s a reminder of the time constraint.”

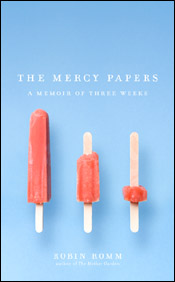

“The heart of this book was written quickly, during and right after my mother’s death,” writes Robin Romm. “Though I tried to keep the pages in a box once I’d gotten the facts down, they’d call out to me when I sat down to write fiction. It was like some weird affair.” The result is her newest book, The Mercy Papers: A Memoir of Three Weeks, a heartbreakingly honest account of her mother’s final weeks. Check out her recent interview with SMITH’s Chris Teja, and read an excerpt below.

“The heart of this book was written quickly, during and right after my mother’s death,” writes Robin Romm. “Though I tried to keep the pages in a box once I’d gotten the facts down, they’d call out to me when I sat down to write fiction. It was like some weird affair.” The result is her newest book, The Mercy Papers: A Memoir of Three Weeks, a heartbreakingly honest account of her mother’s final weeks. Check out her recent interview with SMITH’s Chris Teja, and read an excerpt below.

+++

No one comes up to the loft except me—no one ever has—so it hasn’t changed much in the ten years I’ve been gone. Green thumbtacks secure to the wall a Thai shadow puppet of a naked man made out of goat hide. A framed Lichtenstein poster—a relic from my parents’ first house, in Nashville—leans against a bookshelf. In high school I wove a peacock feather through the latch in the skylight. It’s ratty looking now, covered in dust. Pine needles sit trapped between the screen and the glass.

There’s a knock on the door. For a moment, I think it might be my mother. And this thought makes me absurdly happy—if she can get up those stairs, she’s not really as sick as she pretends to be and the secret will be exposed. Because I’ve always felt that somewhere in that failing, graying mother the healthy mom waits, the mom of my childhood who sang show tunes with too much earnestness, who dashed around to meetings in tailored skirts with matching blazers, who bought me body glitter and maroon tights and then shook her head when I wore them. If she could just force through this facade of illness she would emerge vibrant. She would realize that she could put on her nice checkered blouse, her jeans, and soft shoes, and walk with me downtown, past potted plants and children eating ice cream. The world, dumped over on its side, would assume its old shape, would restore itself to the world I knew before this, the world meant for my family.

But it’s my father. His hair sticks up in front, accentuating the lack of hair behind it. His stubble looks transparent, like slender pieces of plastic growing from his chin.

“Robin,” he says. He’s not used to playing the go between. That has always been my mother’s job. “You need to go downstairs.”

“No,” I say, even though I know I’ll go. “I’m not here to get yelled at.” Mercy, sensing tension, gets out of the bed and disappears beneath it.

“I know,” he says, slumping against the banister outside the room. “Just go downstairs and talk to her.”

My mother is parked by the fireplace. She crosses her arms and clamps them to her abdomen. When pissed, she used to storm out of rooms, fling herself around corners, slam stacks of paper against the battered kitchen tile. You never saw her face, just her compact form disappearing, reappearing. Now I see the minutiae of rage—the way her lashes quiver as her eyelids spasm. The way she grinds her teeth.

“I’m sorry,” my mother says. She doesn’t look sorry, she looks like she’s just seen a tiny explosion out of the corner of her eye. “We don’t have time for this.”

This only makes me angrier—that we’ve all been placed at the mercy of her disease, that it’s trapped us in this house, warping even our arguments. It’s not an apology she’s giving me, it’s a reminder of the time constraint.

“Fine,” I say, pinching the skin on my arm. I can’t look at her. I wish I were back in Berkeley. I wish I were somebody else—one of my fresh-cheeked friends in graduate school who for the last nine years took time for granted. Someone who didn’t have to think about each day, whose cup of coffee on the deck in the morning didn’t feel so fucking temporal.

The kitten struts by us on her way to the litter box. My mother and I both stare. Lily feels it. She turns to look at us. She seems to be thinking something; there’s a spark in her eyes. Maybe she’s contemplating her power, her role as a peace provider, distracter, dispenser of balm. I try to imagine what it would be like to be this kitten, to be helpless and innocent, to walk to the litter box completely in the moment. To feel warm and full and settled. To be loved in a simple, untarnished way. Lily narrows her eyes. Then, with her back to us, she squats and pees on the hardwood floor.

From The Mercy Papers by Robin Romm. Copyright © 2009 by Robin Romm. Reprinted by permission of Scribner, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc, NY.

You’ll find it almost unattainable to come across well-educated parties on this content, and yet you appear like you understand what exactly you’re talking about! Regards