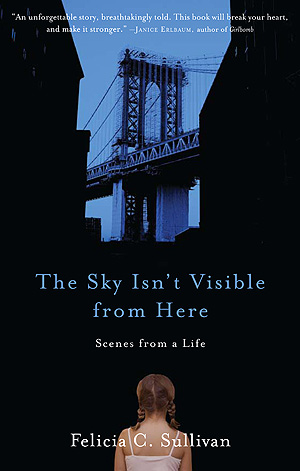

EXCERPT: The Sky Isn’t Visible From Here by Felicia Sullivan

Tuesday, February 5th, 2008

In Brooklyn, my mother and I lived with a man named Avram who taught me two sentences in Hebrew: I love you and I need five hundred dollars. His body was covered in hair as thick as wool, but his skin was slick, smoothed with baby oil. He never left the house without Afrin nasal spray and toothpicks. Avi drove a station wagon with buckets of paint, turpentine, and brushes cluttering the backseat. On the way to school he always warned, “Whatever you do in the dark comes out in the light,” as if he knew a secret of mine that he would ferret out. But I was ten then; I read Judy Blume and wore mismatched socks. I’d already learned how to keep my secrets hidden away, safe.

In Brooklyn, my mother and I lived with a man named Avram who taught me two sentences in Hebrew: I love you and I need five hundred dollars. His body was covered in hair as thick as wool, but his skin was slick, smoothed with baby oil. He never left the house without Afrin nasal spray and toothpicks. Avi drove a station wagon with buckets of paint, turpentine, and brushes cluttering the backseat. On the way to school he always warned, “Whatever you do in the dark comes out in the light,” as if he knew a secret of mine that he would ferret out. But I was ten then; I read Judy Blume and wore mismatched socks. I’d already learned how to keep my secrets hidden away, safe.

Avram was a man who spoke little, so whenever he spoke, you listened. I wonder how it was that he introduced my mother to cocaine: whether there were words at all or if it was simply a pouch of white in his moist palm and a promise of omnipotence. They went from smoking joints while watching Dynasty and passing commentary on Sammie Jo or the silliness of shoulder pads — it was 1985, but Avi and my mother still donned bell-bottoms and paisley, trying to remain in the seventies, that wild-child decade, for as long as they could — to cutting up lines of cocaine. Later, I’d hear my mother crying out “Avi!” their heads smashing up against the headboard. My walls shook.

I imagined them at Brighton Beach, lapping up fat lines with cut straws. They were like any other couple on the beach, drinking malt liquor until they were a little drunk. But then they drank some more. They passed a roach between their fingers, taking tokes. In broad daylight, they dabbed seawater under their noses, inhaling any remnants of coke. They hoarded their highs. I pictured them digging their heels deep into the soggy sand, feeling the gravel between their toes. My mother would marvel at the hot sun dipping into the waves, which had turned black. The water beckoned, but she would inch her body up the shoreline because she felt both comforted by and frightened of the ocean. She would smile then, but only slightly, ashamed of her teeth, which were yellowed and fanged. My mother vehemently avoided the dentist and rarely let anyone see her teeth. To the world she was fair and sexy. While my mother’s and Avi’s cheeks flushed and their necks turned pink, I would be home alone, sitting on the grates of the fire escape, watching the black squirrels desperately scavenge for food in the trees, waiting for her and Avi to come home.

My mother owned a pair of dark red Pumas with dirty white laces. Bits of rubber had frayed from the sides; the soles were so worn that the cotton from her slouchy socks poked through. Whenever she squeezed her feet into the sneakers, one, then the other, she would yank on the laces, hard, and double knot them, rabbit style. She usually put them on when she was going to fight someone, but often she wore them to work because they were comfortable, unlike her work shoes, which pinched her feet. You never knew if she was on her way to work or to a brawl. She called the Pumas her shit kickers.

If provoked, she would pounce on anyone, all five foot two of her, and slam her fists into their face, blinding them with punches. If ever I were teased at school, pushed or picked on, braids tugged, I kept it secret. Living on perpetual tiptoe, I learned not to rouse her.

Dressed in her hideous pinstripe waitress uniform, she walked home early from work one day, past my schoolyard, and waved at me, her little green order pad nestled in her belt. I couldn’t tell if she came by to greet me or to sniff out a scuffle. In the schoolyard, Tamika strutted toward me, her thick braids slapping her chin, the kinky ends scratching her cheeks. I clutched at my black velvet skirt, pouffed out by layers of cheap organza beneath, the ribbons of my white ruffled blouse sticking to my sweaty skin. It was class picture day for us fifth graders, and my mother had braided my coarse, curly hair into two fat pigtails and tied them with red ribbons to match the ones on my blouse. I looked like an idiot.

Tamika pointed at me and laughed. “Silly bambina blanca!” she said. She poked a chubby finger into my rib cage and my legs buckled. Her friends surrounded me in a half circle, snorting. Elsa giggled. Raquel sneered. Soft squeals rose from my throat. I choked them down quickly. My mother, who was standing at the curb smoking a Kent 100, stomped up in the Pumas.

“We got a problem here?” she asked, hands planted firmly on her hips, cigarette gripped at the corner of her mouth. Her breathing was easy, calm. My mother was fearless; if you’d put a gun to her head, her pulse wouldn’t have broken seventy. She waited patiently for Tamika to respond. She would wait all day if she had to; pull up a chair, smoke through her pack, buy another. Because she lived for this drama: making people squirm, breaking them down. And then she gave Tamika the look, brows knitted, pupils constricted — her glare pulverized you, sucked the air from inside out. Tamika shivered. I felt very small.

Tamika dragged the sole of her sneaker from one side to the other as if she were drawing an invisible line between herself and my mother. My mother sucked her teeth. Spitting the cigarette out, she repeated, “You got a problem?” The cigarette lay on the ground, burning to the filter.

“Ain’t no problem here,” Tamika said. Her crew eased back, their feet making careful steps.

When my mother turned to me, her face softened. She retied the ribbons on my braids, adjusted my skirt. Her long fingernails picked at bits of fuzz on my blouse, and with one sweep she wiped off any traces of lint. Once my mother turned her head, sneakers skidded on the ground as the girls sprinted toward the school entrance door, which they flung open. I pulled away and lowered my head. I could have died. I could have melted into the asphalt in shame. And nothing would be left but my velvet skirt, polyester blouse, and scarlet ribbons.

After that day, my mother made it her routine to pass by on her lunch hour and wave. Her hair was always pulled back into a tight braid, her skin stretched tight, as if it were plastered against her face. With a free hand, she smoothed her scalp, and all the flyaway strands obeyed and buried themselves beneath the mountain of rubber bands that held her hair in place. Every morning she lathered Maybelline Tawny Beige foundation into her skin, creating a tan mask — dark tan, she could be Dominican; lighter tan, she could be Puerto Rican — even though everyone in the neighborhood knew we were white people blending in. Her transformation was dramatic: She’d enter the bathroom Irish and fair, thick coats of blue mascara and peach lipstick would follow the foundation, and when she left for work her skin would appear several shades darker. Only her neck betrayed her paleness. Years ago, when she dated black men, she lathered on the make-up even darker and spoke with a Spanish accent. When she slept with white men, she was Rosina Sullivan, the pasty white girl.

Kids became scared of friendship with me. One wrong word, a slight nudge on my shoulder, a sly joke, and my mother would come running in her red Pumas. Palming each other’s backs, the Dominican girls huddled in a tight circle, “Todos sabes acerca de tu mamá.” Black girls tried to act tough, shoulders erect, heads held high, but they hushed in my presence. Everyone in Boro Park knew about my mother; she awed them because she was beautiful and dangerous. She appeared never to sleep, as if she even rested with one eye open. She was nothing like the other mothers, who held court on stoops, arms folded in, talking about everything and nothing.

“I can’t breathe,” my mother said one Saturday night, shaking me back and forth in my twin bed. My Glo Worm nightlight was hot and burned dimly in the room. I dreaded the weekends because they were always her worst time. Free from the obligations of waitressing — of waking at five in the morning, of pressingher uniform and wiping her sneakers clean — she was free to play, to go out dancing, linger at the beach, or worse, spend nights out with Avi, nights that always ended up with them laughing and snorting coke until dawn.

Sitting on the edge of my bed now, she pulled my sheet down with the weight of her body, which had whittled down to bone. I rubbed my eyes and grabbed my glasses from the nightstand. The room smelled of her perfume, Love’s Baby Soft, a mixture of sweet powder and vanilla musk.

I sat up and said, “You want me to call a cab?”

“Yeah,” she whispered, her breath straining as if it would be her last.

I wasn’t fooled. She wasn’t dying. This scene had played out before. I would sit in the cab in silence while she panted. We would enter the hospital, me clutching her shirt, her recoiling in disgust, “You’ll wrinkle my shirt!” I would wait for her in the dingy waiting room, a putrid brown film coating the walls like wallpaper, lime green and orange plastic oval chairs lumpy with chewing gum. Passing time by watching the clock’s hands, I knew it might be hours before her return. Later I would hear the familiar stomp in the hall, and there she would be, appearing confident, as if nothing had happened.

Sometimes she dropped the powder-blue pamphlets in the trash can outside the hospital; other times she left them on the floor in the back of the cab. I snatched one once and it opened like an accordion. Facing Your Addiction, it read. I crumpled it into a tight ball, surprised by how neatly it fit in my hand.

And here we were tonight, back to where we always started, me calling the car service to Maimonides Hospital and her convinced that this trip would be her last. As I slid out of the two layers of blankets, all my stuffed animals fell to the floor in a collective thump. My mother eased her frame into the imprint I had made in the bed and then stared at the wall.

“I’ll call the cab,” I said.

“Hurry,” she said, placing her hand on her chest. The other hand held a cigarette, which she drew slowly to her lips. Blood trickled from her left nostril. She sniffed it back.

I ran back into the room and scooped up a book from my nightstand. Waiting-room material.

Before I even said the address: “We know where you live, kid.”

The dispatcher’s voice was throaty, sympathetic. On my tiptoes, I reached high to place the receiver back into the cradle. I stood in the darkness of the kitchen, my feet cold against the linoleum squares.

“Did you call?” She was in the living room now; her voice had grown louder. I looked at the door, at the various locks, chains, and deadbolts, and I wanted to run.

“I called,” I said.

“What?” she hollered, dragging her feet across the carpet, making her way into the kitchen.

“You have to put your shoes on,” I said. She had on her pink slippers, the ones with the pebbled white soles. I powered past, grabbed her shoes, and kneeled. My eyes could barely focus on the tattered laces; my lids kept easing down like a silk curtain dropping. I concentrated on tying a double knot. If I could just get this one knot. If I could just do this.

“Get the Pumas,” she said, coughing. Her body was volcanic. Under her breath, she kept saying, “Damn you, Avi.” The cigarette slipped from her fingers onto the kitchen floor. From the street, a car horn beeped twice, waited a few minutes, beeped again. I threw my coat over my Strawberry Shortcake pajamas and helped my mother down the four flights of stairs. We took it slow and my mother was impatient. “Jesus, Lisa, can you move any slower? I could be dying here.” She called me Lisa because Avi couldn’t pronounce my name and they decided it was easier than Felicia. Lately she used my given name only when she was angry or in public. She leaned into me, even her skeletal weight becoming hard to bear. Still she crushed cockroaches all the way down. I gripped the plastic bag with the Pumas. My knuckles turned white when she proudly yelled, “I got seven of the fuckers!”

Avi was gone, away on another one of his trips to Atlantic City, playing blackjack and roulette with the hope of scoring big. The kind of score that buys you a month’s supply, keeps away the men who call and ask about the money you owe, when and how will you pay it. And I wondered about what kind of boy Avram had been. What kind of boy grows into a man who offers up cocaine like fairy dust, sprinkles it everywhere my mother walks, and then leaves for weeks at a time?

“Maimonides Hospital, right?” the driver asked, staring at me in the mirror.

“Is there anywhere else?” I answered, sliding into the leather seat.

A few weeks back, I had walked the seven blocks from school to the shabby diner on Thirteenth Avenue where my mother worked. The windows were smudged and dirty from fingerprints and the grease that rose from the grill. The menu, taped on from the inside, was filthy. Butter had soaked through the “Specials” and grape jelly was smeared over the “Meat” entrees.

My mother stood behind the counter, refilling ketchup bottles. She’d taken all the half-empty ones and turned one bottle upside down so that the mouths met, executing this task with such precision that she didn’t allow a drop of the paste to spurt out of the bottle and stain the counter. When she saw me, she traipsed over to the soda fountain and filled a tall glass with ice and Coca-Cola. She placed it in front of me as I climbed onto the stool, my hands pressing the leather seat for leverage.

She leaned her elbows on the counter and drummed her fingers on her chin. “Grilled cheese or blueberry muffin?”

“Muffin, of course,” I said. Within moments, my mother slid a steaming mushroom-shape mass before me. I picked at the crust on the edges, circling the muffin’s top, breaking off bits of bread and berry, then nibbling down to the minor scraps. A man stared at me, his fleshy pink lips curved into a smile.

“Got a system there with that muffin, kid?”

And then suddenly my mother was screaming. The whole of the diner was paralyzed, which is not to say that mouths paused in midbite or feet froze in a shuffle, but the customers set their forks down and voices fell to a hushed murmur. They stared. She was her own circus attraction. All the muscles in her face tightened. Blue veins punched through the sides of her neck. Spit flew in the air.

“You don’t think I hear what the fuck you’re saying?” she shouted. She marched out from behind the counter toward a table where two men were seated. Both wore baseball caps stained with oil and soot. They clutched their spoons, frightened. Hands on her hips, she spat in the face of the thinner man in a Camel cap.

The other waitress begged, “Rosie, your kid!”

My mother glared at her, then turned back to the man. “You got something to say about me? You want to say it to my face?”

The other man’s fingers clutched a strip of bacon, his mouth buried in a white beard. “Moving around the tables kinda fast is all we we’re saying.”

“A little too awake,” the other timidly added. “A little too much of the powder.” He tapped his nose.

The bearded man slouched back in his seat. “You should be ashamed, with your kid here and all. Shit, Rosie, everyone knows what you’re doing.”

He chuckled and my mother laughed with him. She tilted her head so far back I thought it would snap. I didn’t know if I should run or stay put. I just wanted the men to go away, for her to walk over and refill my soda. Didn’t they know not to provoke her?

The restaurant was reduced to a collection of inverted faces, of nudging and whispering as her laughter snowballed. From the kitchen, the cook journeyed toward her, but before he could reach her, before he could hold her back, she grabbed the bearded man’s plate and smashed it over his head. Yolk slid down his face as he jumped out of the booth, knocking down his Coke. He slipped on the soda and collapsed on the floor. My mother smiled and turned to me.

“I’ll see you at home,” she said, waving me away.

The yellow cracks in the ceiling had spread since the last time I’d sat in this hospital waiting for my mother. The loudspeaker dangled from a thin black ceiling wire. People whispered, played spades, and fiddled with their radios until they were hailed to the white rooms behind the plaid curtains. Beside me, a small boy shifted from side to side, his honey skin luminous in the false overhead lights. We were watching Benny Hill on a television that hung, like the loudspeaker, from the ceiling. The boy wore white Pampers and stunk of urine.

My grip tightened around the handles of the plastic bag that held the Pumas. I picked at the plastic, tearing off slivers and dropping them to the ground like snowflakes. Furious with my mother, I shredded the plastic until the shoes tumbled to the floor, barely making a sound when they hit, one then the other.

A young woman with fluid dark hair pulled back in a loose ponytail clutched a clipboard. The nurses behind the station laughed. I heard static from their radio. I leaned over my chair, picked the Pumas off the floor, and held them to my nose, breathing in. They smelled like my mother, the perfume and sweat from her beige nylons.

This was how it always felt, waiting for my mother.

Beautifully written. I love the imagery; it’s almost as though you are there.

Very powerful. I almost cringed as if I were the target of your mother’s pounce. That’s how strikingly you pulled me into your life.

It will be useful for college students to check https://writemyessay4me.org/blog/computer-science-career out. Here you can learn more about computer science career