The World Tour Compatibility Test: Beijing

Thursday, December 14th, 2006

by Elizabeth Koch

Part travelogue and part convoluted love story, The World Tour Compatibility Test is a series of true stories set in exotic locales, as two American writers decide whether to break up or move in together. Click to catch up on Shanghai.

We wake up early and re-stuff our bags and head to the airport again, this time with John. Tonight we’re due in Beijing, where, as ludicrous as it sounds, Todd has managed to set up an Opium reading. Todd has delusions of Opium grandeur, which lands him on stages in clubs in Stockholm, translating Opium submissions into Swedish, a language he’s never spoken, in a country that speaks perfect English. Which is part of why I love him.

We wake up early and re-stuff our bags and head to the airport again, this time with John. Tonight we’re due in Beijing, where, as ludicrous as it sounds, Todd has managed to set up an Opium reading. Todd has delusions of Opium grandeur, which lands him on stages in clubs in Stockholm, translating Opium submissions into Swedish, a language he’s never spoken, in a country that speaks perfect English. Which is part of why I love him.

John’s driver is even more reckless than usual. He swerves to the right and clips a biker, who tips over and then picks himself up again, as if skidding across concrete in a baby blue business suit were typical pre-work affair. John speaks to the driver in Mandarin.

“I’m sorry,” John says once we’re inside the airport. “I have problems firing people. The Onion’s a nice enough guy — he just doesn’t drive very well.”

Legroom on Air China is nonexistent. Todd and I sit in the middle of the middle aisle and tilt our legs sideways, English horseback style. An hour goes by, and the plane doesn’t move.

“Is this normal?” I ask John.

“Highly. The average time a plane sits on a runway in China is two hours.” He continues scrolling through his Blackberry.

“What, no announcement?”

“Oh, they made an announcement. They said, ‘Sit back, relax, and enjoy the short flight to Beijing.’”

Todd is writing and I like to interrupt him when he’s working. I put my arms around him and we kiss long and hard. I want to keep kissing him even though John’s elbow is in my spine and Todd’s skin smells like B vitamins.

Todd pulls back and makes a face, “You taste like…yuck.”

“Dried carrots. From the Shanghai market.”

“Don’t ever eat those again.”

A pretty flight attendant appears with a few bags of something wrapped in cellophane.

“To wash your hands,” I say, nudging Todd.

She holds out a package. “Dum-yum?” The man to Todd’s right opens his package, pulls out a yellow sponge, and eats it.

…

Pollution drapes Beijing like dusty mosquito netting, layered and itchy and riddled with bugs. When we exit the airport, our mouths and eyes fill with greenish clouds of sulfur.

“Oh my god,” Todd says, and spits. “People get used to this?”

John shrugs.

Beijing is nothing like Shanghai. Shanghai has a silly side — turnpikes there feature giant plastic trees blooming with butterflies. There’s nothing funny about Beijing. Here the skyscrapers are thick and round like giant gavels slammed to the ground in a furious, raging hurry. Powdery filth rises off the streets, off the lampposts and concrete walls, and collects in your nostrils and tries to choke you. Women on bikes wear Darth Vader visors, faceguards that resemble a welder’s protective shield. Crowds of people stand motionless at bus stops, mouths covered in surgical masks. I try to take pictures, but the road is furrowed, and the camera jumps. The vibrations here are merciless and menacing; they shiver down your spine so your feet go numb and your muscles ache with torpor. If Shanghai is a Bugs Bunny cartoon, Beijing is Midnight Express.

Beijing is nothing like Shanghai. Shanghai has a silly side — turnpikes there feature giant plastic trees blooming with butterflies. There’s nothing funny about Beijing. Here the skyscrapers are thick and round like giant gavels slammed to the ground in a furious, raging hurry. Powdery filth rises off the streets, off the lampposts and concrete walls, and collects in your nostrils and tries to choke you. Women on bikes wear Darth Vader visors, faceguards that resemble a welder’s protective shield. Crowds of people stand motionless at bus stops, mouths covered in surgical masks. I try to take pictures, but the road is furrowed, and the camera jumps. The vibrations here are merciless and menacing; they shiver down your spine so your feet go numb and your muscles ache with torpor. If Shanghai is a Bugs Bunny cartoon, Beijing is Midnight Express.

We are staying, once again, with an Opium contributor. Roy lives in the Chaoyang district, home of the 2008 Olympic Park. I cannot imagine stuffing more humans in these crowded streets, let alone large families of fat Americans with baby carriages and beer coolers. I’m already planning to never come back again.

We exit the elevator on the 20th floor of an 18th story building (the Chinese don’t like the number four, so they pretend it doesn’t exist), and Roy Kesey greets us in the hallway. Roy is broad-shouldered and water polo slim with a storyteller’s smile. He teaches creative writing at the University of International Business and Economics, which sounds so perfectly incongruous in this cryptic city of codes that I don’t question it. His wife, Lu, is a Peruvian diplomat and so drop-dead gorgeous I keep asking her questions so I can stare at her a little longer.

We’re running late for the reading, so Todd and I hurry to the guest bedroom — a stark cube of a space with a low bed and a narrow window near the ceiling. I refuse to shower because I’m too tired to towel off. Todd grabs his razor and leaps over Roy’s tiny children, Chloe and Thomas, who think it’s a game, and try to run through his legs while he yanks off his shirt.

We’re running late for the reading, so Todd and I hurry to the guest bedroom — a stark cube of a space with a low bed and a narrow window near the ceiling. I refuse to shower because I’m too tired to towel off. Todd grabs his razor and leaps over Roy’s tiny children, Chloe and Thomas, who think it’s a game, and try to run through his legs while he yanks off his shirt.

“Hey Roy — did the buttons come?” Todd asks from the bathroom. Todd designed Opium World Tour buttons as a surprise to me, but he couldn’t resist showing me the design before we left. It’s a picture of us cheek-to-cheek and smiling so huge we seemed connected, like a Cheshire cat with two heads.

“I couldn’t track them down,” Roy says through the door. “I was on the phone with FedEx all morning.”

“Fuck.”

Buttons are one of Todd’s things. I met Todd via his buttons, at a literary magazine event, an inception story that I pretend embarrasses me, but I sort of like the saccharine poetry of it.

“Hey,” he’d said, stepping between me and a friend. “You look like you could use a button. Put this on.”

He pinned an Opium button to my sweater. This frail boy with flyaway hair, wearing a Green Lantern t-shirt with a pinstriped blazer, charmed me out of an almost inconsolable depression over another man, one I had no business brooding over in the first place. Todd followed me around that night with a breathless exuberance that I told myself would quickly wear thin. This is fine for now, I thought as we clanged teeth in a taxi. Won’t last.

Roy hands me an espresso cup. “Turkish coffee?”

“You saved me,” I say.

The reading is held at the Bookworm Cafe, the main English-speaking bookstore and literary hangout in Beijing, located on a trendy street called Sanlitun. The strip is thick with bars and chattering, carousing expats. A photographer named Lucy ushers Roy, John, Todd and me out back, where there are no bars, no coffee shops, and no cars. The five of us gaze over a wide runway of dirt to the far end, where a tiny, dilapidated shack appears close to crumbling. Roy tells us the property had been confiscated by the government; eminent domain is so everywhere there isn’t even a term for it. Dozens of families once lived here and were “asked to leave.” This one family refused. For whatever reason, no one has come after them yet.

The reading is held at the Bookworm Cafe, the main English-speaking bookstore and literary hangout in Beijing, located on a trendy street called Sanlitun. The strip is thick with bars and chattering, carousing expats. A photographer named Lucy ushers Roy, John, Todd and me out back, where there are no bars, no coffee shops, and no cars. The five of us gaze over a wide runway of dirt to the far end, where a tiny, dilapidated shack appears close to crumbling. Roy tells us the property had been confiscated by the government; eminent domain is so everywhere there isn’t even a term for it. Dozens of families once lived here and were “asked to leave.” This one family refused. For whatever reason, no one has come after them yet.

“I want a photo with that house,” Todd says.

We climb on a small hill of dirt and rubble and thick, ropey weeds and take rock star pictures, the skeletal home trembling in the background.

During the reading, the audience is larger than we’d expected, padded mainly with Roy’s students, who sit still as stone with mystified expressions throughout. Perhaps they have trouble with the slang in our stories, words like “retard” and “bag of dicks.”

Todd thanks the audience afterwards. “We had buttons for you guys, but I think the Communists confiscated them.”

The room goes silent, a breath-holding, blood-draining silent that hurts my eardrums. Please Todd shut up right now.

“But why am I apologizing? You guys must be used to that.” I half expect the floor to drop out and Todd to fall through it, or a sniper to put a bullet through his brain. John Leary covers his face with his hands and shakes with laughter.

Afterwards a few audience members — middle-aged Chinese men in suits — approach me and bow. One speaks English.

“Your magazine very interesting. Poetry!”

“Not so much poetry.”

“Your husband, he funny. But…” the man shakes his head gravely.

A large group of Roy’s friends and Bookworm groupies head to the Pavilion, a new bar and restaurant built on 3,500 sqm of shimmering green gardens. Giant flat screen televisions are stationed throughout, and barbeque buffets flank the social area, in honor of the Ghana/U.S. World Cup match. I know we’re losing because Todd keeps punching John Leary in the shoulder and shouting, “Jackass move!” I know I should care about the game, and I do in a way, but I’m not watching. I’m appreciating the salad and firm sausages and boiled potatoes on my plate, foods with shapes and colors I recognize.

A large group of Roy’s friends and Bookworm groupies head to the Pavilion, a new bar and restaurant built on 3,500 sqm of shimmering green gardens. Giant flat screen televisions are stationed throughout, and barbeque buffets flank the social area, in honor of the Ghana/U.S. World Cup match. I know we’re losing because Todd keeps punching John Leary in the shoulder and shouting, “Jackass move!” I know I should care about the game, and I do in a way, but I’m not watching. I’m appreciating the salad and firm sausages and boiled potatoes on my plate, foods with shapes and colors I recognize.

Our group spills across a long picnic table, and across from me sits an American twenty-something from Seattle. I keep asking her questions, but I’m too drunk and shaking with hunger to listen well.

“He’s still missing,” she says.

“Who, your father?”

“No no — my friend. A filmmaker. He was here doing a documentary on the underground Christian movement and got arrested six months ago. No one’s seen him since.”

“What’s his name?” As if I might know him.

“Wu Hao. His sister spoke to him once, a few weeks after the arrest. She said his voice was strained, like someone was listening.”

“Jesus.”

The table shakes and beer bottles tip over and roll to the ground. Todd is jumping up and down on the bench with his fists clenched, the reddish-black sky flaming above his head. “Fuck!”

America has lost the match. We’re knocked out.

…

A sharp whirring, a drill through metal bars maybe, wakes us at 7 a.m. The bed is hard and so low to the ground that my luggage is blocking my view of the wall. The room smells funny, like rotted fruit. I’m hungover. Todd is too, I can feel it before he speaks. His hands wrap around my arm and squeeze.

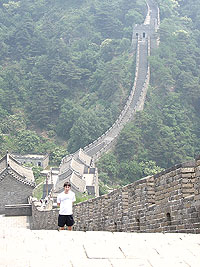

“Love me!” he whines.

I get up, and he pulls me back. I pry his fingers off me and lock myself in the bathroom to prepare. Today is the Great Wall day. I am happy, and not because I give a damn about the Great Wall. I am happy because I went to bed stuffed and woke up stuffed, and when I am hung-over and full I don’t want to be touched. I’m often one or the other, which doesn’t leave much time for affection, but frankly, Beijing is too dirty for affection. I have enough grime on my own body without Todd rubbing his all over me.

I get up, and he pulls me back. I pry his fingers off me and lock myself in the bathroom to prepare. Today is the Great Wall day. I am happy, and not because I give a damn about the Great Wall. I am happy because I went to bed stuffed and woke up stuffed, and when I am hung-over and full I don’t want to be touched. I’m often one or the other, which doesn’t leave much time for affection, but frankly, Beijing is too dirty for affection. I have enough grime on my own body without Todd rubbing his all over me.

John Leary, the saint, pays for a driver to take us an hour past the smoggy, tourist-trampled section of the wall. I sit in front, Todd in back. He tries to talk. I don’t want to talk.

“Do you want me to stop talking?” he asks.

“I don’t know.”

“Are we fighting again?”

I say nothing.

“Elizabeth.”

“Can we just not talk for now? Is that okay?”

“Sure,” he says, with forced levity.

We drive beneath a canopy of feathery trees that dip into the road. The air seems a bit clearer out here, the sky a tepid suggestion of blue. An hour goes by. We say nothing.

By the time we reach the steps of the 3,948-mile long wall that took 12 centuries to build, Todd and I might as well be staring at the empire state building, or the Eiffel Tower, or a flagpole in Palo Alto. When we are distant from one another, we are nowhere. I take the steps two at a time, and he follows. At the top we take pictures because that’s what you do when you’re visiting the Great Wall. We stand in front of a watchtower, looking sick and pale against the white-gray backdrop.

“Not much of a view,” I say.

“Maybe there was a dust storm.”

The heat is oppressive and menacing, and I want to be alone in it. “I’m going to go ahead.” I move away from him, and don’t look back.

Ten minutes later I pass a mule. It’s huge and fat with a shiny ass. It lifts its tail and dumps greenish, crabapple things. I turn back to look for Todd, to celebrate this massive creature with a cock the size of a sledgehammer, but he’s not there.

An hour later I make my way back to the top entrance.

An hour later I make my way back to the top entrance.

“Hi,” he says mildly.

“Hey, were you waiting long?”

He shrugs.

Getting up the Great Wall is brutal; going down is child’s play. Our options are a ski lift and toboggans. We choose the toboggans — first me, then Todd, coursing down the silver chute at speeds that would get us ejected from most amusements parks. I almost ram the woman in front of me. “Go, lady!” I shout. Todd laughs, which means he has forgiven me.

On the way home we ask the driver to stop by an indoor market called ‘Lee and Lee,’ where cheap Chinese furniture is sold. The market is three floors tall and sectioned off into small rooms stuffed with silk screens and bamboo desks and black lacquer banquets and tall clay pots and card tables. I don’t like haggling. I’d rather just pay what they ask, 700% markup or not.

“Elizabeth, you have to haggle. They expect it.”

After one or two tries, I cannot stop haggling. I am a haggling machine. I don’t want any of the things I see, I just want to haggle. One woman, pretty with paintbrush bangs and pouty lips, is closing shop when I stop her and point to a sturdy wooden bureau with a slatted front.

After one or two tries, I cannot stop haggling. I am a haggling machine. I don’t want any of the things I see, I just want to haggle. One woman, pretty with paintbrush bangs and pouty lips, is closing shop when I stop her and point to a sturdy wooden bureau with a slatted front.

“500,” I say. It’s about $65.

“No,” she says. “3000.”

“No way. 750.”

“You cheap!” she shouts. “2500. Last price.”

“2500 too high,” I say.

We go back and forth like this for 20 minutes. She finally throws up her hands. “It late. You go,” she says, and shoos us out. She starts to shut the gate. I look at Todd. He shrugs.

“Okay okay okay,” I say. “Your price. I’ll buy at your price.”

The girls stops and looks at me skeptically.

“Your price,” I repeat. “500.”

She throws back her head, opens her mouth, and shrieks a terrifying, nail-on-chalkboard protest that skips my heart. She slaps her drink in the garbage and storms away from us.

Todd runs after her.

“Wait wait wait,” he says, tugging on her shirtsleeve. “She means your price — 2500 — don’t you, E-beth?”

The girl’s nose is pink, her chin visibly wobbling.

“Oh, god, yes, I’m really sorry, I got confused — 2500 is fine.”

She unlocks the gate and takes us inside. “You made her cry,” Todd whispers, proud of me.

…

“I can’t believe we’re going to dinner like this.” I look down. I’m wearing tiny shorts last seen on Three’s Company and a once white tank top that appears to have been curried. Todd’s hair is slick across his forehead.

“I can’t believe we’re going to dinner like this.” I look down. I’m wearing tiny shorts last seen on Three’s Company and a once white tank top that appears to have been curried. Todd’s hair is slick across his forehead.

“Shit.”

By the time we arrive, Roy and Lu and their children are already there, at the popular family-style Xiangmanlou restaurant. Roy orders duck that comes in five different sections: skin, white meat, gray meat, organs, and bill. I break off the tip of the bill and eat it.

Todd orders soft foods, steamed buns and gooey bok choy, and I order crunchy dishes, cucumber salad, fried carrots, and steamed prawns. When the food arrives I tear through the prawns, tail and shell included. Lu’s five-year-old son watches me. He picks up a shrimp head and swallows it before Lu can stop him. She tips back his chin and reaches inside his throat to retrieve it.

John Leary has been tied up with clients, and races in as the gravied meats and bamboo leaves are congealing. He sits on the other side of Todd. “How was the wall?”

“She got a video of the toilet out back. So she’s happy.”

“The view was kinda dusty.”

“Oh? It should’ve been clear way out there.”

I shake my head. “We bought furniture,” I say brightly.

“She made a lady cry.”

“I didn’t mean to.”

Todd stands suddenly. “I love Bei-jing,” he shouts, coming down hard on the jing, like jingle bells. I want to break my chopsticks. “I’m gonna launch an Opium in Mandarin!”

“Oh sure, Opium Magazine in China,” I say. “That’ll go over well with the authorities.”

I look up and John is glaring at me from across the table. “Would you quit stomping on Todd’s joy?”

Damn John Leary for seeing only this in me. I don’t want to kill Todd’s joy. I want him to share it with me. I want to be up there, in the air, where he is, but I don’t have the stamina for that kind of happiness.

…

We go back to the apartment and I’m ready for bed. “Drinks?” Roy asks. John looks at Todd.

“Why not?”

I go to the bedroom to pack, half expecting Todd to follow me. He doesn’t. I shower and go back to the living room and sit next to Todd.

“It’s too hot,” he says, and pushes me away from him.

Roy points to the bar area by the kitchen, I pour myself a clear, smoky liquid from a diamond-shaped bottle and sit on the floor, a few feet from Todd, who doesn’t seem to notice. Roy tells a story about his first teaching job, about his attempt to cross the border from Serbia into Croatia during the war — about the gunshots that whizzed by his ears, and the night he spent face-down in a swamp while the border patrol hunted him down. Roy’s spirit is wild and Lu hugs her knees to her chest while he’s talking, frowning and picking her toes.

“I’m going to bed,” I say after a while.

“Night,” Todd says.

I blame John for this uncharacteristic rebellion. I crawl into bed with The Safety of Objects, which I’ve stolen from John’s bookshelf. The walls are thin and I hear John ask about me.

“Is she okay?”

“She’s in bitch mode.”

“Did I say something?”

“It doesn’t take much.”

Todd comes to bed half an hour later.

“Hi.”

I turn the page.

“You’re not talking to me. Again.”

“Nope.”

He slides in bed next to me, kisses my shoulder. “I thought we were going to do it in every country.”

“You fucked that one up.”

He sighs and rolls on his back. “You can’t keep doing this.”

Watch me.

——————————–

The journey continues….in Tokyo

Wonderful descriptions of the pollution, the crowds. Makes it seem less exotic and, I suppose, accounts for the mood swings. I’m really enjoying the trip, I just wish she were.

Every time I read ” Perhaps they have trouble with the slang in our stories, words like “retard†and “bag of dicks,†I laugh for about twenty minutes.

This travelogue is more fun than a bag of dicks! Next stop: Our hearts!

I love the video… She’s so adorable in it, it makes you realize she’s not as grumpy as she makes herself out to be. We love you Elizabeth!

You guys are way too kind. I’m blushing.

Please don’t stop.

What an odessey. You write just like you see life. You are so melodramatic. Its great. You have such a quirky sense of how things are, its qute delghtful. Interested to hear what happens next. In the meantme, could somebody give that woman a hug.

Some people in my family have been to China, and some haven\’t, but read this blog. Thanks, Elizabath Koch, for inspiring all kinds of interesting travel talk instead of politics or religion at my Christmas dinner table…